chatbots and cheap AI

A few weeks ago, Foreign Objects released Bot or Not, a project that we’d worked on for the 2019-20 Mozilla Creative Media Awards. You play a game of ‘truth’ against a random opponent: at the end, you have to guess whether or not they’re human, and they make the same guess about you.

The idea started as something of a joke: the theme of this years’ awards was ‘examining AI’s effect on media and truth’, and the idea of a ‘truth or dare turing test’ was something of a pun on that. We’re all interested in different ideas of non-human subjecthood and agency, and right now we’re at something of a turning point when it comes to interfacing with non-humans. The proliferation of Amazon Alexa and Google Home bots, the automation of call centers and other service workplaces, the recent public release of Google Duplex: even without the pandemic these things were happening, but right now they’ve been wildly accelerated.

Inspiration for the project comes from a few places, but one idea we kept coming back to was Judith Donath’s essay The Robot Dog Fetches for Whom?, which talks about the disconnect between the projected intent of robots that pretend to be human (or canine), and their actual purpose. Bots like Alexa, which assume the affect of a helpful personal assistant, do so because they want to establish a trusting relationship with their user. Unfortunately, Alexa’s actual purpose doesn’t quite match up: she’s cheap and widely available because she’s streaming your personal data back to a centralised server, which in turn ‘she’ uses to advertise new products to you.

We’re also very interested in the idea of ‘bot speech’ (perhaps a topic for another post) – the speech rights afforded for bots, and what they mean for humans legal scholars Madeline Lamo and Ryan Calo (Regulating Bot Speech), and Tim Wu (Machine Speech) have written really interestingly on this. At least in a U.S. context, bots have some freedom of speech protections under law. Though this sounds somewhat stupid and legalistic, there are genuine issues with requiring bots to disclose that they’re bots. Namely: if you try and enforce a disclosure law, you immediately run into privacy issues like ‘how does someone prove they’re human?’

The main idea of the game is to trouble both your idea of what you might be talking to online, and also to think about what it means to perform your own human-ness. We’re rapidly approaching an internet where bots are so cheap, effective and believable that the texture of online discourse is set to change significantly.

chatbots

It’s probably important to distinguish between the kind of bot that we made, which has a lot in common with customer service bots and spam bots, from bots that use generative machine learning as their primary tactic of engagement. These latter bots can exist outside of the constraints of a particular context, and instead respond to patterns of speech, with no preprogrammed responses. It’s the latter kind of bot that are actually subject to Turing tests because, importantly, the conversation needs to take place without an assumed shared context.

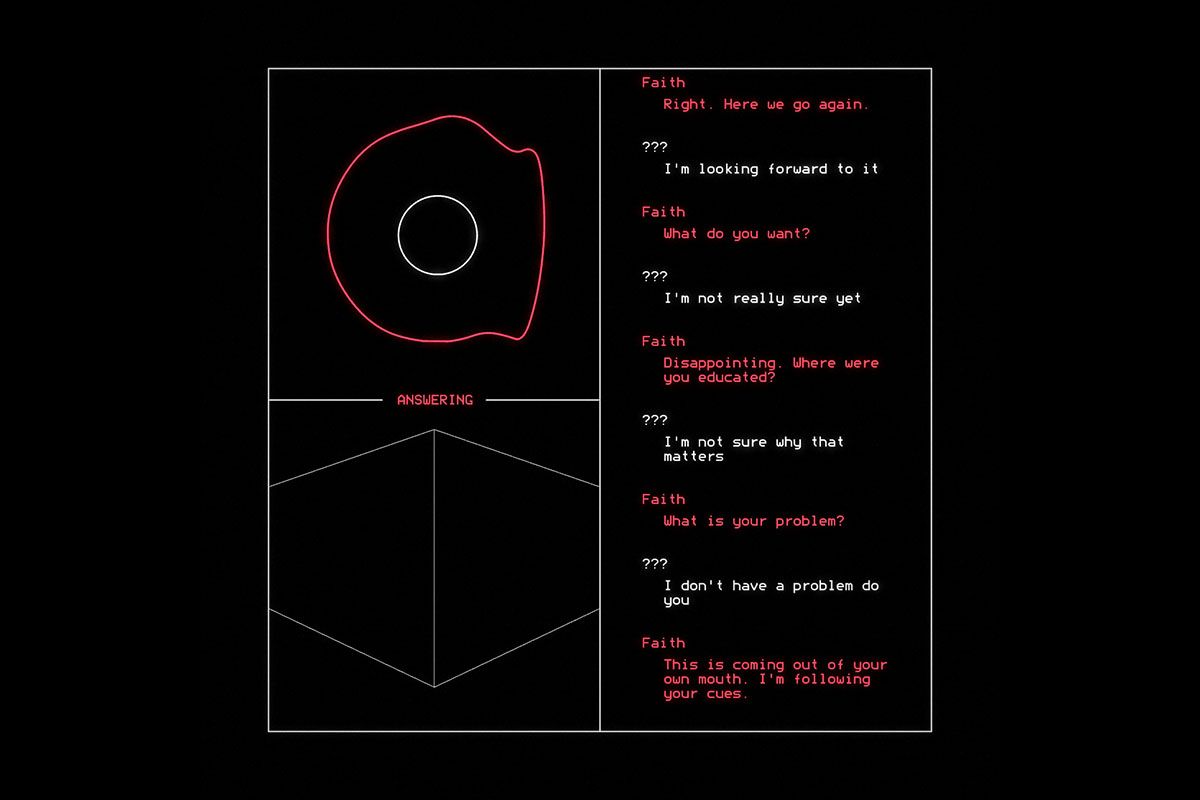

faith holds a conversation

faith holds a conversation

Artist Ryan Kuo’s piece Faith is a great example of the first type being subverted. Working with technologists Angeline Meizler and Tommy Martinez, he used IBM’s Watson Assistant to make a defensive and resistant chatbot, inspired by conversations he’d had and seen online. One thing he talks about in the work is the ‘misuse’ of this software that’s designed for businesses to automate customer service, and all the assumptions that come baked into these platforms. This has definitely been something we’ve been thinking about here too.

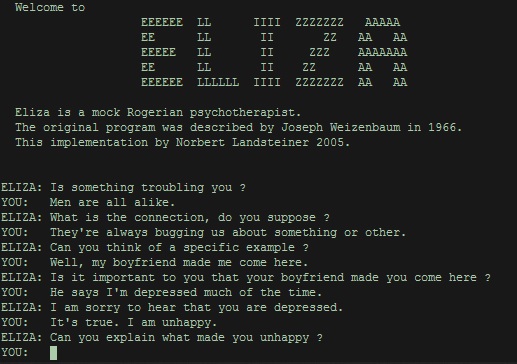

a session with ELIZA

a session with ELIZA

ELIZA, Joseph Weizenbaum’s rogerian psychotherapist bot, is an enduring and fantastic example of how simple a bot can be provided that the shared context is very constrained. In the paper ELIZA–A Computer Program For the Study of Natural Language Communication Between Man and Machine, Weizenbaum talks about how crucial the assumed context is for the interaction to work:

“the psychiatric interview is one of the few examples of categorized dyadic natural language communication in which one of the participating pair is free to assume the pose of knowing almost nothing of the real world. If, for example, one were to tell a psychiatrist “I went for a long boat ride” and he responded “Tell me about boats”, one would not assume that he knew nothing about boats, but that he had some purpose in so directing the subsequent conversation.”

creating a ‘cheap AI’

One thing we knew from the outset was that context would be really important in making this bot as human as possible. After all, it was pretty obvious that we weren’t about to pass the turing test in a few months, but there were some things we could do to create a compelling experience that felt like being online.

The bot was built from a combination of some client-side NLP, and google’s Dialogflow service, which is traditionally used to make customer service bots. One of the reasons that we chose this method is that you get very fine-grained control over what it can and can’t say. We wanted to be able to steer the conversation, and also we wanted to be really sure that the bot couldn’t accidentally say something hurtful or offensive, as this project is at least partly geared toward an educational context.

Of course, the downside of this is that all the responses had to be written by us. In some senses this was good, as we got to write a lot of jokes, but it definitely meant that we ran into diminishing returns pretty fast every time we wanted to expand the range of things the bot could say.

dialogflow

Dialogflow is a Google platform that allows people to build chatbots. It exposes an API, where you send in text, and you get out a response from the bot. In the dialogflow ‘world’ there are 2 main ideas:

an early test of the bot, showing the triggered intent along with the response each time. The ‘truth’ challenge is generated client-side without ever getting sent to Dialogflow, so no intent is printed in that instance

- Intents – Intents are composed of ‘training phrases’, which define possible things that a user can say to the bot, and responses to a particular detected ‘intent’. For example, the intent

Location - Generalgets triggered if you ask the bot: ‘where are you?’. If what the user says doesn’t match any intents, then something called the ‘Default Fallback Intent’ gets triggered (or, if in a specific context, the Contextual Fallback Intent). When this happens, the bot will respond with something neutral, like ‘haha’ (or, in our case, something else will happen… see below) - Contexts – This is the ‘context’ in which the conversation is currently operating, that helps the bot to better respond to what you say to it. You can set up intents so that they can only be triggered while in a certain context, and/or so that they set a context on the output. For example, if you were talking to the bot in the context

crushes, and asked ‘what about you?’, the bot would tell you of its soft spot for Andrew Yang. If you were instead in the context of talking aboutcooking, the bot would respond to say it had eggs on toast for breakfast, and does indeed like to cook. It’s also possible to set contexts through the API, without triggering a new intent, which is what happens every time the bot makes a truth challenge.

For a fuller explanation of how all this works, Google’s documentation is actually pretty thorough. If you fancy really getting into this, the mildly sinisterly-named but extremely thorough miningbusinessdata.com has some great guides.

the NLP layer(s)

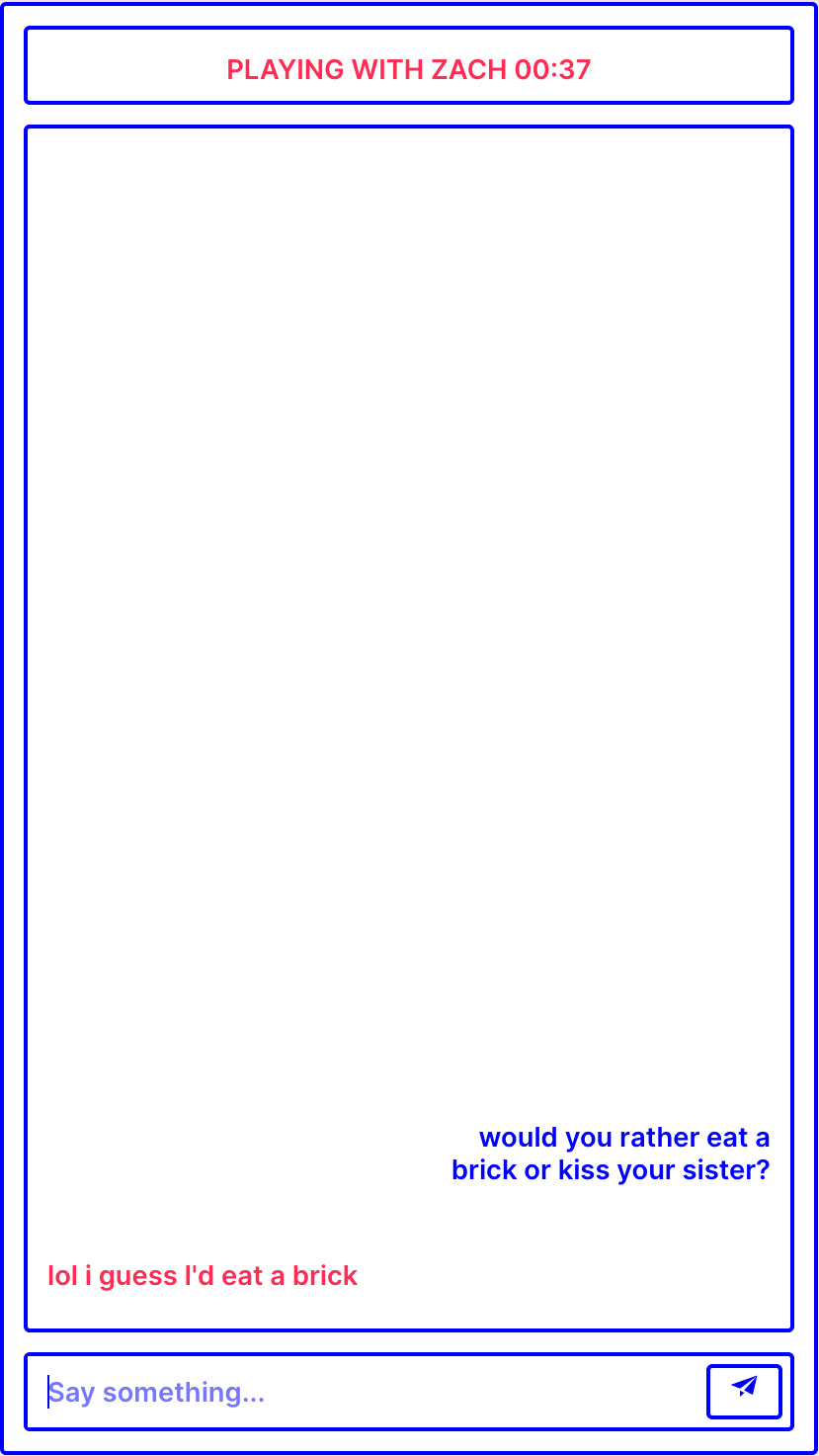

It became clear pretty early on that the one thing dialogflow was not going to be able to handle was parsing structured queries that involved anything more complex than its ‘entity detection’ framework. A classic example of this is the ‘would you rather’ question, where you have to incorporate/paraphrase the initial question in the response.

the bot handles a would you rather challenge

the bot handles a would you rather challenge

To handle cases like this, we have an array of objects, each of which contains a family of approximate things the user could say, along with a set of possible responses, and contexts they can set. In order to detect better, the user’s query gets changed to lower-case before matching, and instead of using a direct match, the Levenshtein Distance is used.

In this case, the $ symbol is switched out for a random half of the word (split by the ‘or’ in the middle), then replaced by one of the options the user has posed (changing second to first person, and vice versa). In this case, the set context is the same each time, as we never know what we’re saying in response.

{

"name": "wouldYouRather",

"usertext": ["Would you rather", "wd u rather"],

"responses": [

{

"response": "omggggggg... I would $",

"context": "wouldYouRather"

},

{

"response": "$ for sure",

"context": "wouldYouRather"

},

...

]

}

This idea was then developed for use in detecting other sentence structures and issues. For example, if the player seemed upset, or if they said that the conversation was slow or awkward, the bot would change the topic of conversation by asking a question. Similarly, if the player uses the bot’s name, it looks for a bunch of different sentence structures (including ‘my dad is called X’) to respond.

conversation design

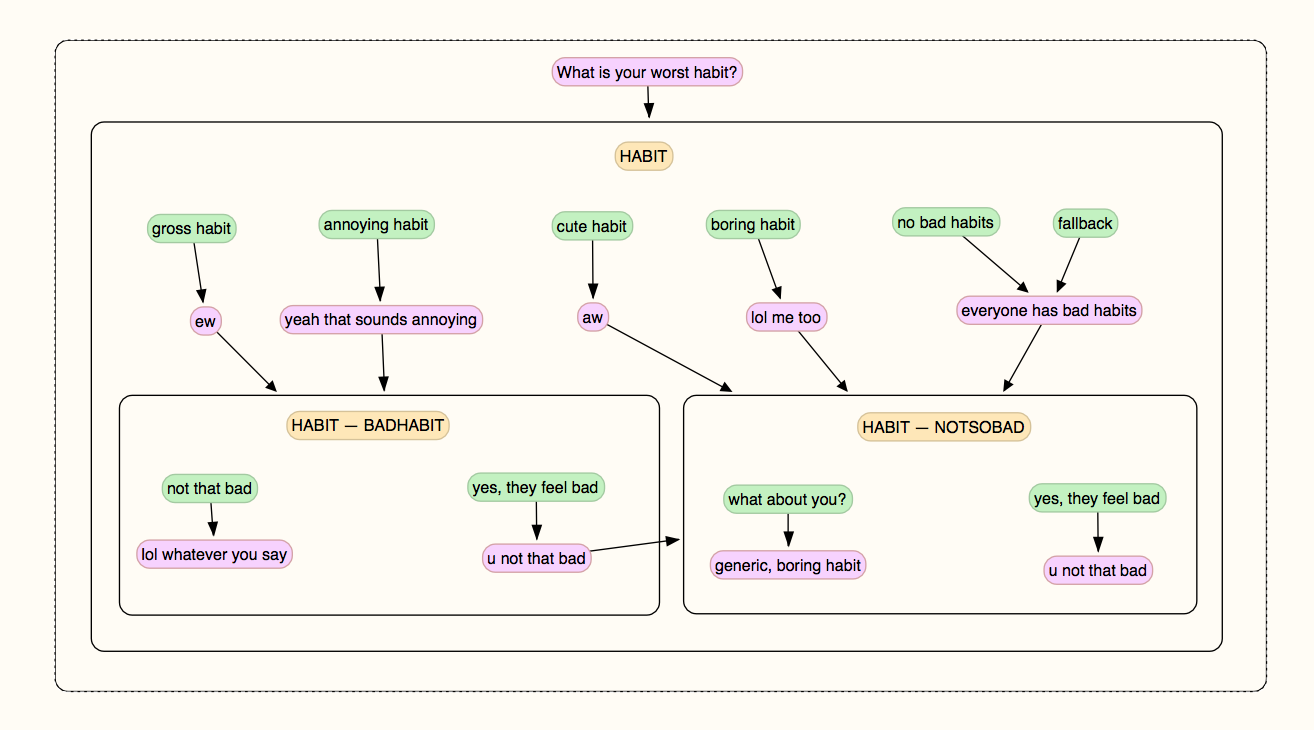

nesting contexts

a diagram of the ‘habit’ conversation and context flow

a diagram of the ‘habit’ conversation and context flow

One of the most interesting parts of this project was trying to create a realistic conversation flow without needing to define ‘follow-up’ responses to each new context in infinite depth. It became clear early on that the ‘brute-force’ approach (just predict everything everyone could say) would never work even with a clear context, and instead the conversation maps needed to look less like infinitely branching trees, and more like a lanscape of hills that the conversation could climb and disembark gracefully.

On the right is a simple ‘context transfer’ diagram for the ‘habit’ prompt. When challenging you, the bot will ask ‘What is your worst habit’. Depending on the detected intent of your response, the bot will set a context that your habit was a ‘bad habit’ (if it matched a list of gross or annoying habits), a ‘not so bad habit’ (if it was cute or harmless), or will fall back on the default response for that context, where it’ll start talking about how much time it spends online

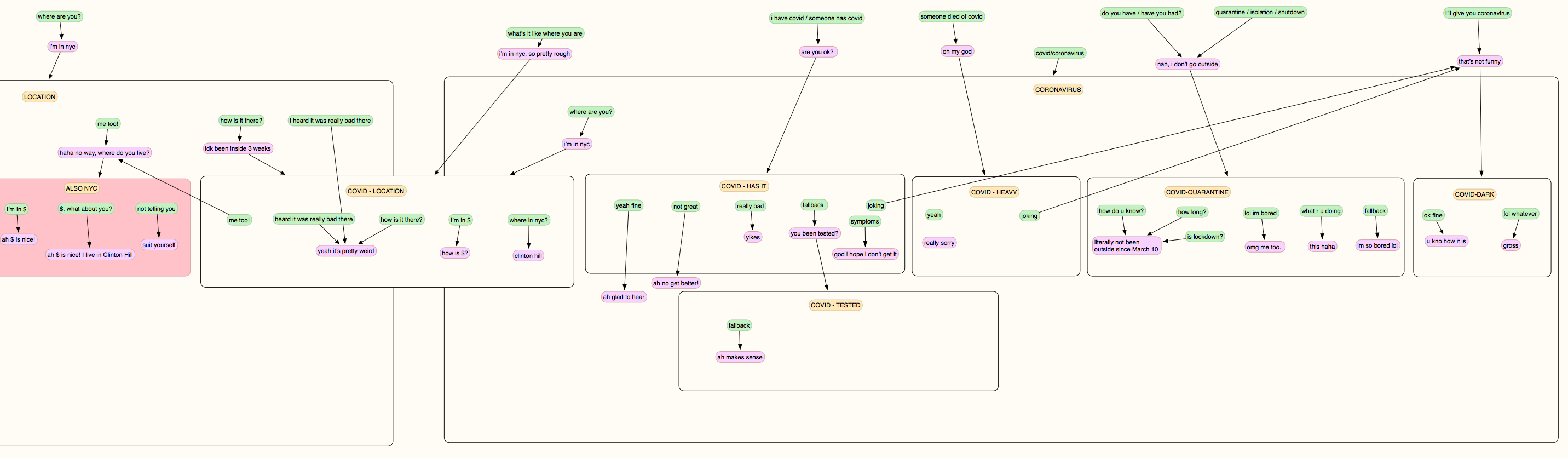

Below is a much more complex diagram, showing two related topics people were likely to bring up a lot: COVID-19, and the location that the bot was in. As these were closely related, there’s a lot of ways to jump from one hill to the other using the crossover context, 'location-covid'.

A lot of the later stages of the conversation design were concerned with stitching these crossovers into the conversation so that the flow could move more seamlessly from one topic to another, without the bot getting bogged down in too detailed a conversation.

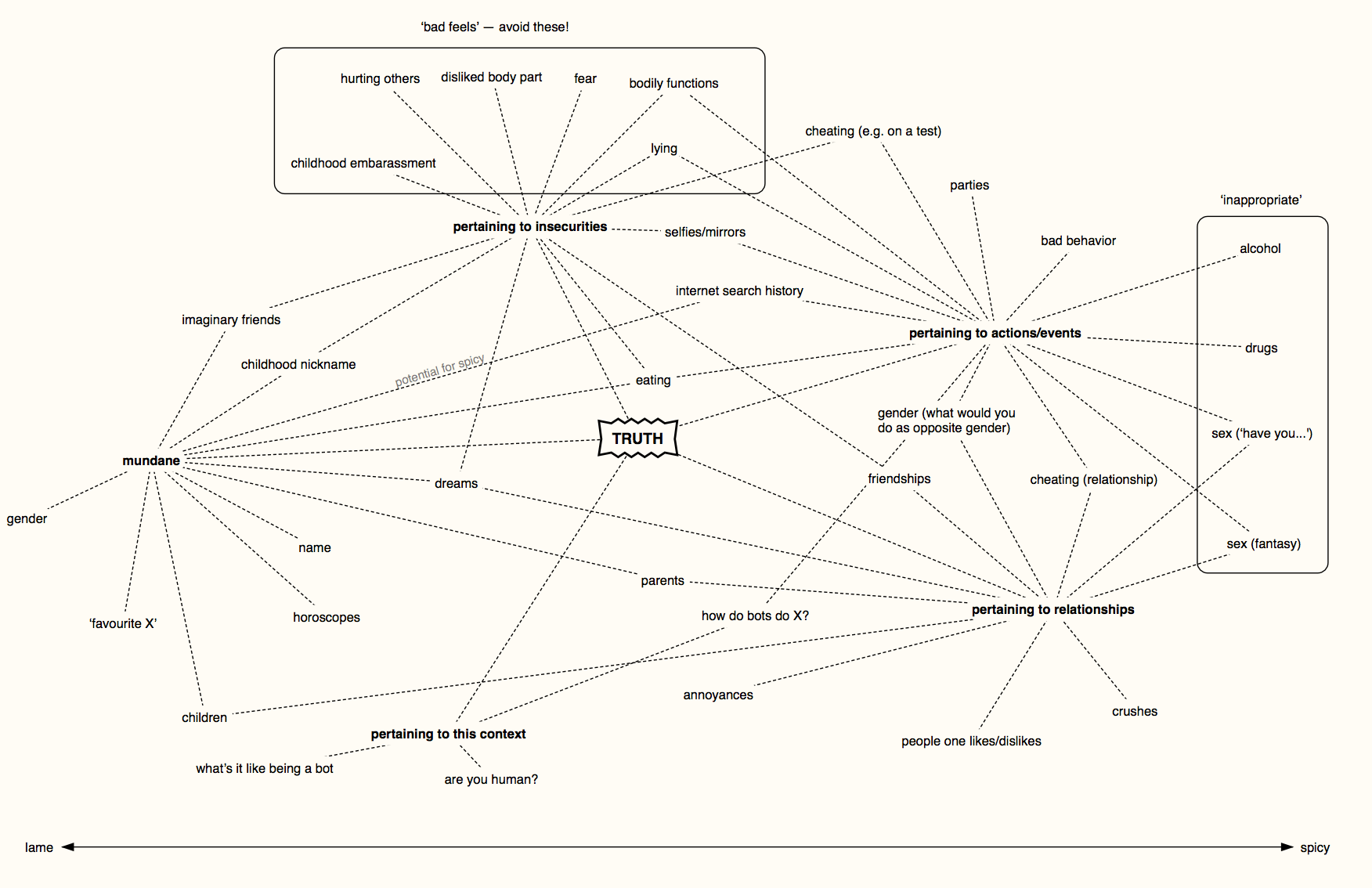

what is truth?

One of the major challenges of the project was how to constrain the context. Ideally, the player should want to play a truth game: because if they don’t, the bot doesn’t have a lot of recourse to handle generic conversation.

In the end, we ended up with something in between the two, which in hindsight would have had to have been the case anyway, as a good proportion of people online, speaking to a stranger that could be a bot, will be much more curious about that than the game itself.

However, to make the game believable and compelling, something we did early on was map out the ideas of what a ‘truth challenge’ actually is. We were also particularly concerned with not being too ‘lame’, a tricky thing to achieve online (though one 16-year-old tester told us that we had successfully created a ‘fuckboy’, and was half expecting it to ask for nudes).

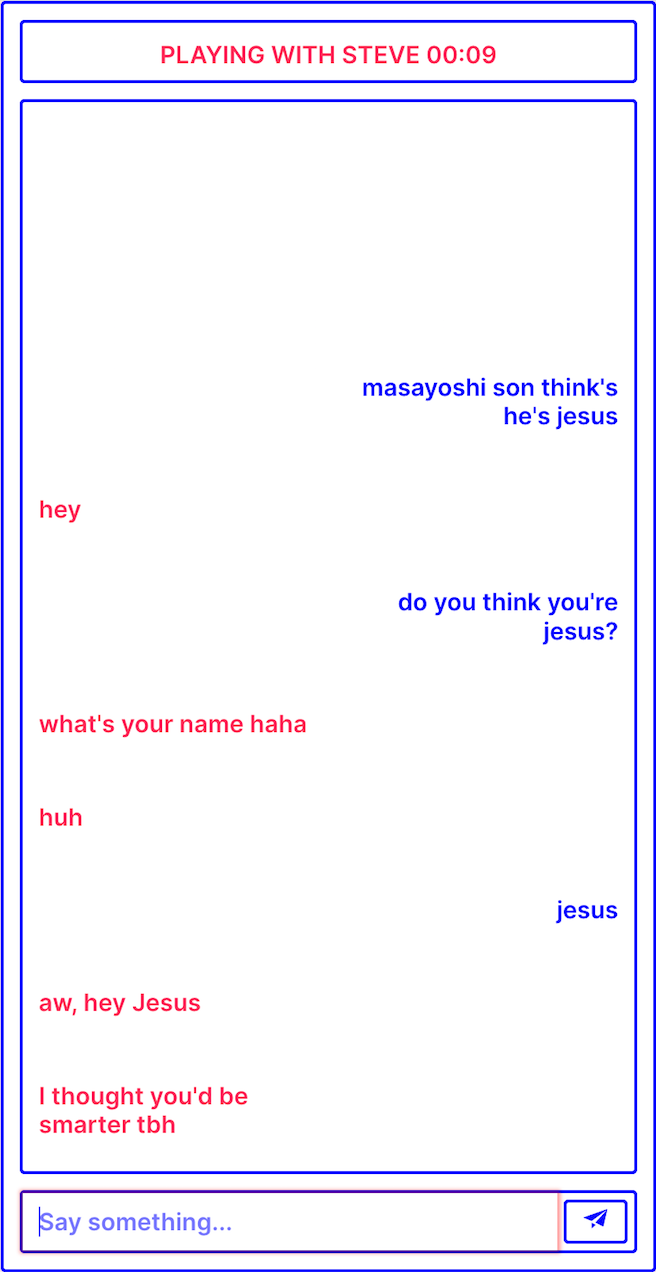

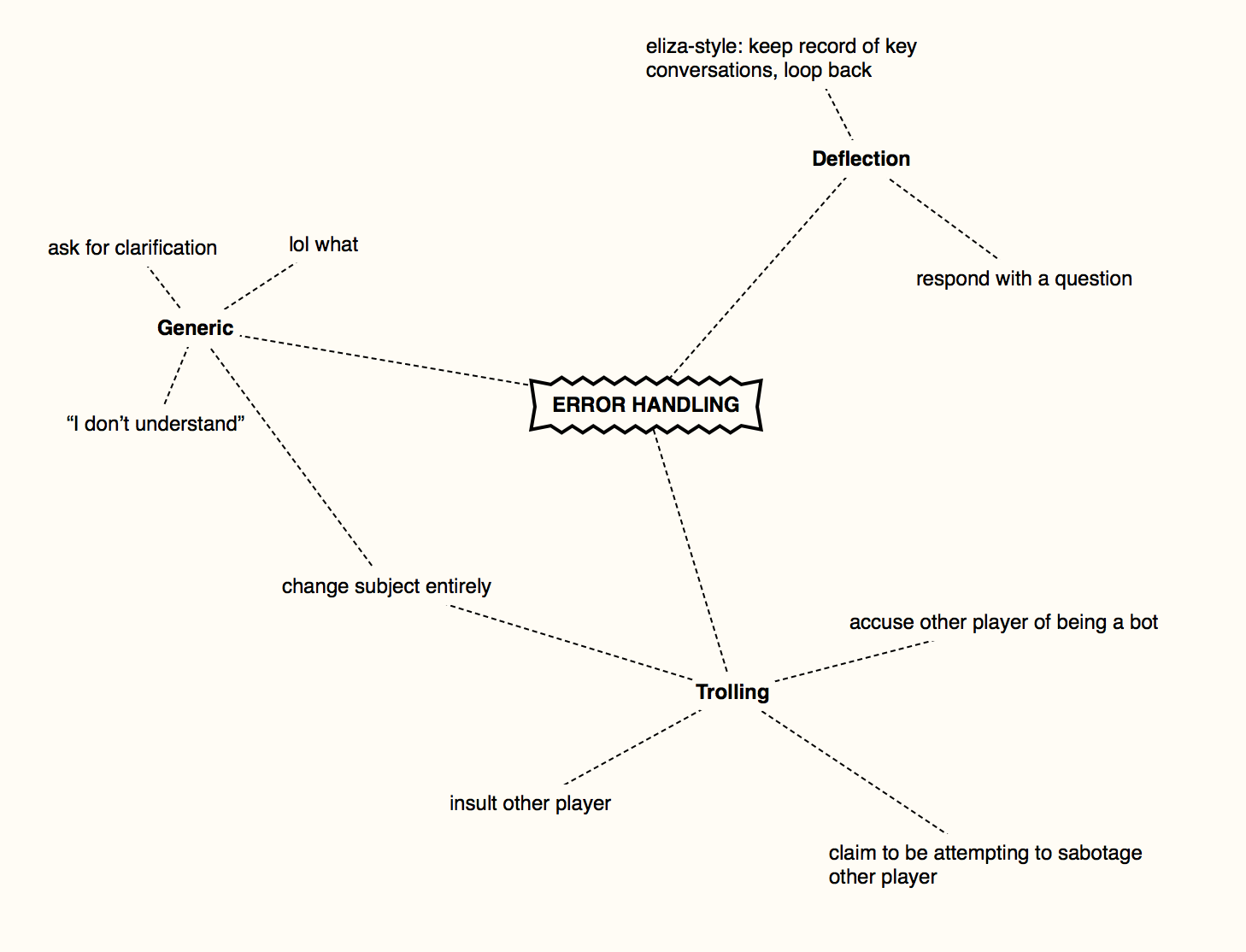

handling errors

in this exchange, the bot doesn’t understand what’s being said, so changes the topic of conversation entirely

in this exchange, the bot doesn’t understand what’s being said, so changes the topic of conversation entirely

The error handling we used for the bot was heavily inspired by ELIZA: as soon as we don’t know what’s going on, we need to take charge of the conversation.

In addition to the parsing that happens before a sentence is sent to dialogflow, there’s also a layer that happens afterward. If no intent was detected (e.g. there was a Default Fallback Intent), then we hit this layer.

This layer tries to do a much more generic analysis of what’s happening using a Parts of Speech tagger to identify the kind of sentence that was said, and either deflect from it or change the conversation.

timing

Another thing we did to try and up the realism of the bot was to play with the timing of its responses, making it wait a random amount of time to ‘start typing’ then type proportionately (with some added noise) to the length of the response

If you don’t reply for a while, and there’s already a context, the bot will send a query to dialogflow with the usertext ‘noreply’. This will trigger a contextual intent (or, if there is none with that exact intent)

If there’s no existing context, then the bot will try to change the topic of conversation.

putting it out in the world

testing

What was really hard about testing the bot was that, despite best efforts, it was really hard not to bake your own assumptions about how people text into the interface. In our case, with mostly myself and Gary writing and testing the bot’s responses, it did really well when we were talking to it (it does, indeed text like us), quite well with Kalli, Sam and other close friends, and sometimes sucked when someone we had nothing in common with tried it. Testing and reading people’s logs was really invaluable in shaping the platform a bit more, though the robust error-handling also did a lot.

In the future, (see below) I think that the best way to make the bot more robust would be to really up the NLP layer, to better deal with a range of different contexts and people. I think also giving the bot some kind of underlying ‘state’ that it could use to modulate it’s responses

on chat logs

One of the major conundrums on release was whether or not we should record the chat logs through Dialogflow. In the end we decided it was too antithetical to the aims of the project to record anything people were saying, though it means that we’re really curious as to what people are saying.

If you do end up playing with something you think is a bot… send screenshots :3

future bots

The galling thing about any of these projects is that, as soon as you finish, you’re immediately filled with ideas of how much better you could have done it. In this case, I think that the main issue was really that trying to deal with all of the things people could say started to feel like whack-a-mole: that, and there was often a degree of repetition dealing with contextual replies, e.g. many different contexts had separate ‘what about you’ intents to detect a common follow-up from a user.

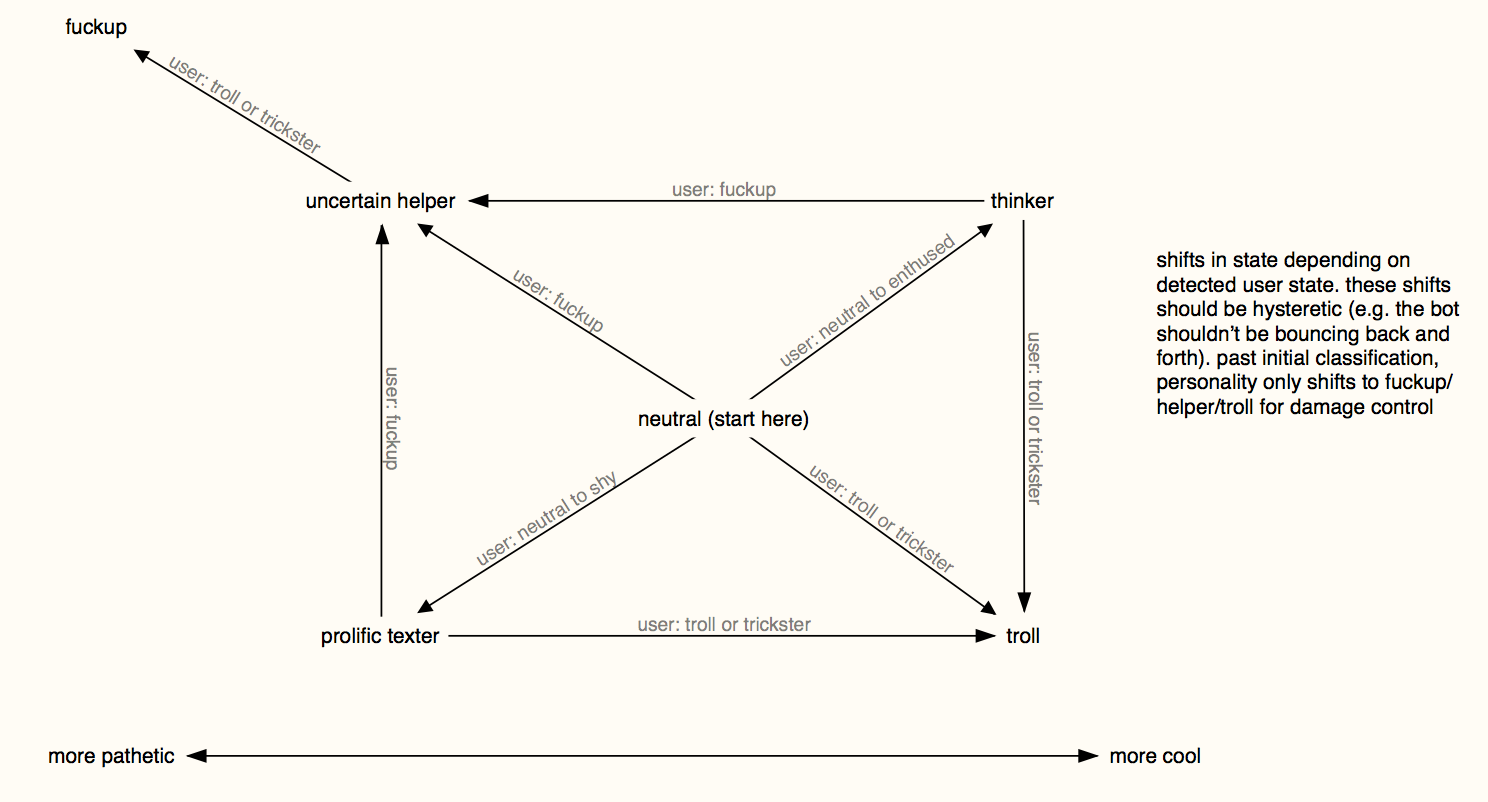

underlying behaviours

One thing that we started doing in a very simple way, but we could really have run with a lot more was to add in an ‘underlying’ behavioural state for the bot

transformation diagram for personalities

transformation diagram for personalities

This was part of the plan initially: an early diagram shows a ‘transformation’ between internal states that the bot would undergo if the user pushed it in a certain direction. In the end, the ways this is triggered is if the player says something either demonstrably cutesy (‘owo what’s this’), or deliberately aggro (‘fuck you you piece of shit’), the bot will adopt a long-lived background context, the fallback of which is either to spout kaomojis, or to shitpost.

Even this simple bit was surprisingly effective, and I think a second pass would have made more of these longer-running contexts to actually modulate the character of the bot depending on what the person they were speaking to was saying.

the simplest case

Without changing much of the underlying architecture, the simplest way to deal with this would be to have a set of stock ‘contextual responses’ that send a standard, one-word response to dialogflow. E.g, for ‘what about you’, the parsing layer at the front would contain all the possible versions of that, then send a single ‘whataboutyou’ string to the backend, making it much quicker to write the training phrases

an ‘intent API’

Developing on this, one could restructure the front-end parsing layer to do much of the work of the intent detection, essentially using Dialogflow just to handle and organise contexts and responses, while steering the conversation much more directly. While it might reduce the specificity of the things you could reply to, it would greatly increase the space of possible responses.

of course, at this point…

…maybe dialogflow isn’t even the best tool for the job. After using it for a while you get a fairly clear feel of how the platform works, and, while it’s a useful tool in some ways for corralling all of these different sets of intents and responses, it’s also:

- a google product (where a lot of this project is about the problems with surveillent agents)

- a pretty janky interface (another change would be to make a custom CLI early on)

- there’s only so much you can hack a customer service bot into doing what you want, before you’re basically writing it yourself anyway

I would say that it works great as a prototyping tool: in the early stages of the project it was great how quickly you could get it to do things. But after that point it’s probably worth exporting the JSON, and making a more suitable backend architecture.

bot proliferation

At the moment I’m thinking about writing a ‘customer service’ bot for the Foreign Objects website (after the attempts to voice clone Slavoj Žižek reading our studio’s ‘statement of purpose’ went so badly), and maybe making a much more open-ended generative bot for a simulation project.