permaculture network

This is a long-overdue writeup of a project that Gary and I worked on last summer, as part of a Schloss Solitude Web Residency Rigged Systems, curated by Jonas Lund. Parts of this are adapted from answers to questions that different people have asked about the projectthanks, Callil, and to Denise Sumi for interviewing us. If you’d like to read some other writing about this piece, it was recently covered by Daphne Dragona for Transmediale’s 2020 print publication, which you can download as a pdf here, and parts are new. An are.na channel for this project exists here, and the code is open-sourced here. The simulation itself is online here.

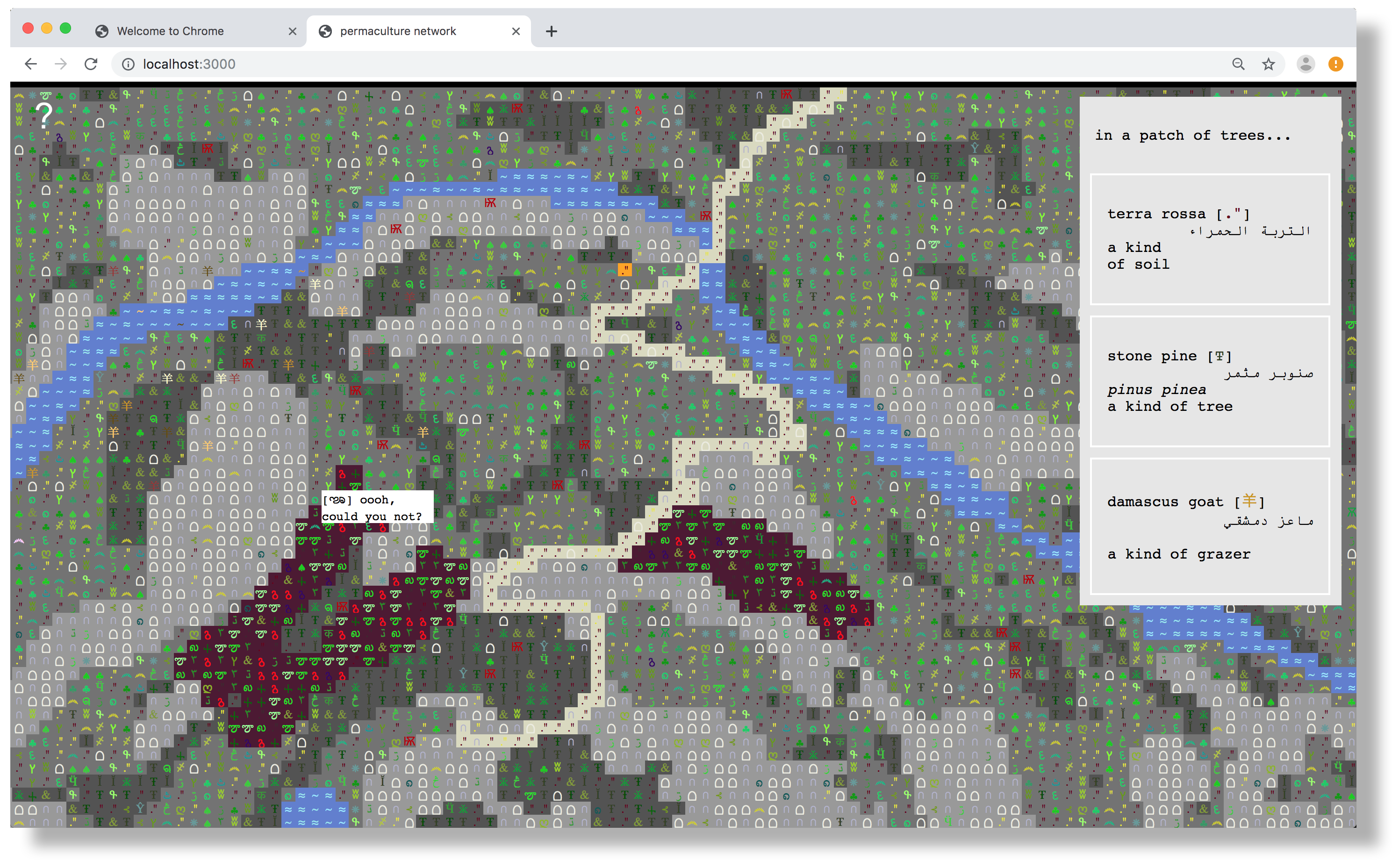

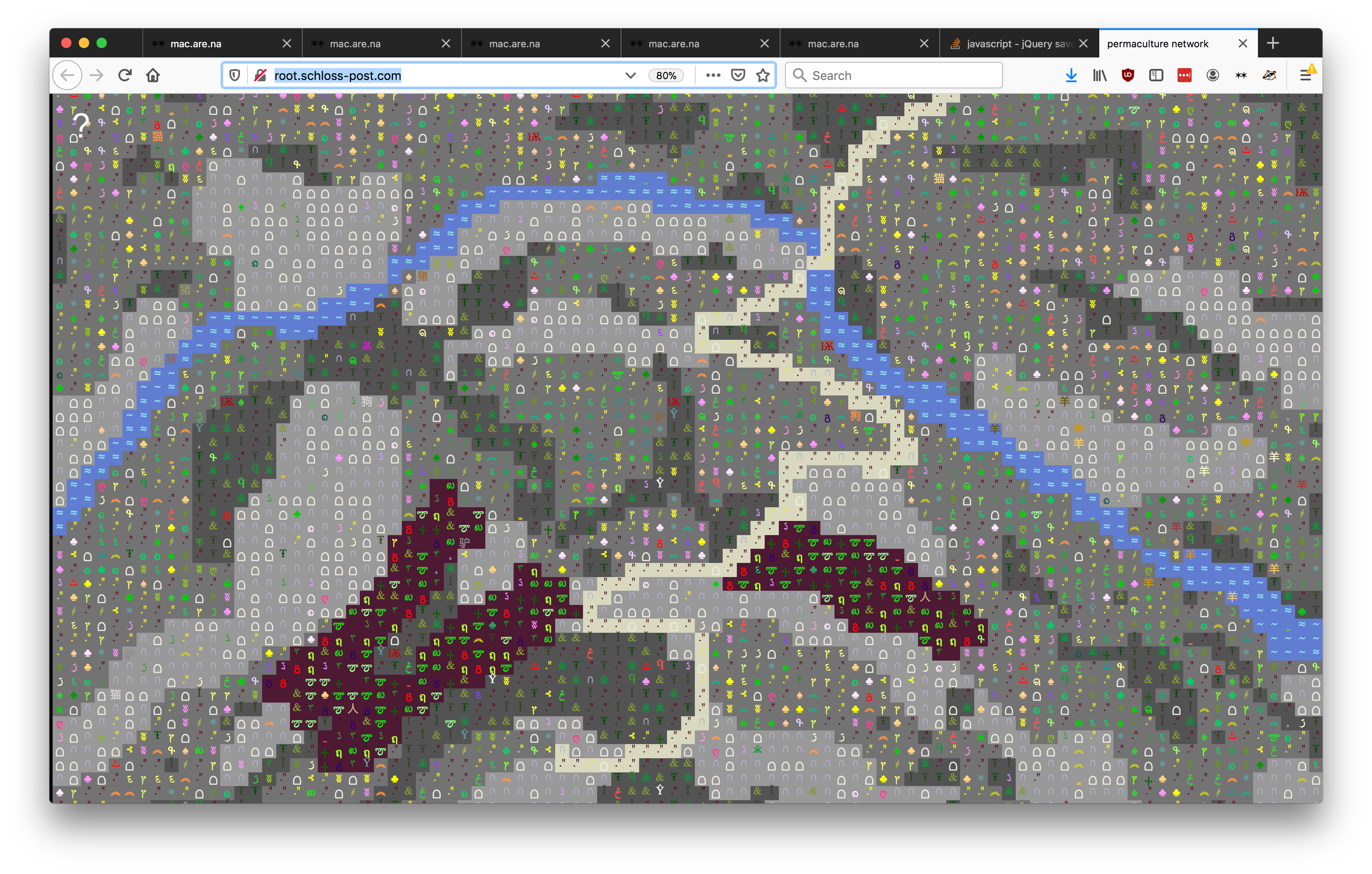

A full view of the simulation

A full view of the simulation

Permaculture Network is an agent-based simulation, a ‘zero-player’ game that was made while we were resident at Sakiya, an art, science and agriculture institution based in the village of Ein Qinniya, Palestine. The project came about in part because we were thinking a lot about alternative representations of land, particularly from the perspective of data-gathering. Sakiya exists on Area C land in the west bank, which Palestinians aren’t allowed to build on (but which is frequently seized by Israeli settlers). One of the main routes by which land in the area is colonised in this way is through data collection: from the British Mandate to the current occupation, there’s a direct correlation between measurement of the land and its qualities and its subsequent requisitioning from Palestinian hands.

a topographical view of Sakiya’s site, which is mimicked by the view of the simulation

a topographical view of Sakiya’s site, which is mimicked by the view of the simulation

Initially, this project was to be the front-end for a set of networked soil sensors on the site, as setting up local soil quality monitoring has been on Sakiya’s roadmap for a little while. Our intention was to find a way to give an feeling of the landscape changing over time and seasons for people external to the site, while the back-end – only accessible to people managing the site – would allow for direct data-gathering, and generate reports about how different parts of the permaculture farm were faring. In the end, we didn’t have the equipment to set these sensors up permeanently, though we’re hoping to do so in the future. More about how they’ll be integrated lower down.

technical details

The simulation explores the ecology of Sakiya through imagined conversations between plants, animals, soil, water, weather, and other human and non-human agents. The nature of these conversations is based loosely on the idea of permaculture ‘guilds’: plants that, when grown together, provide mutual benefit to one another. In as much as was possible, we tried very hard to re-create the actual ecology found on the site. Almost all of the agro-ecological information about the site: the soils, geology, and plant life, comes from a survey of Sakiya by agroecologist Omar Tesdell, and his team at Makaneyyat.

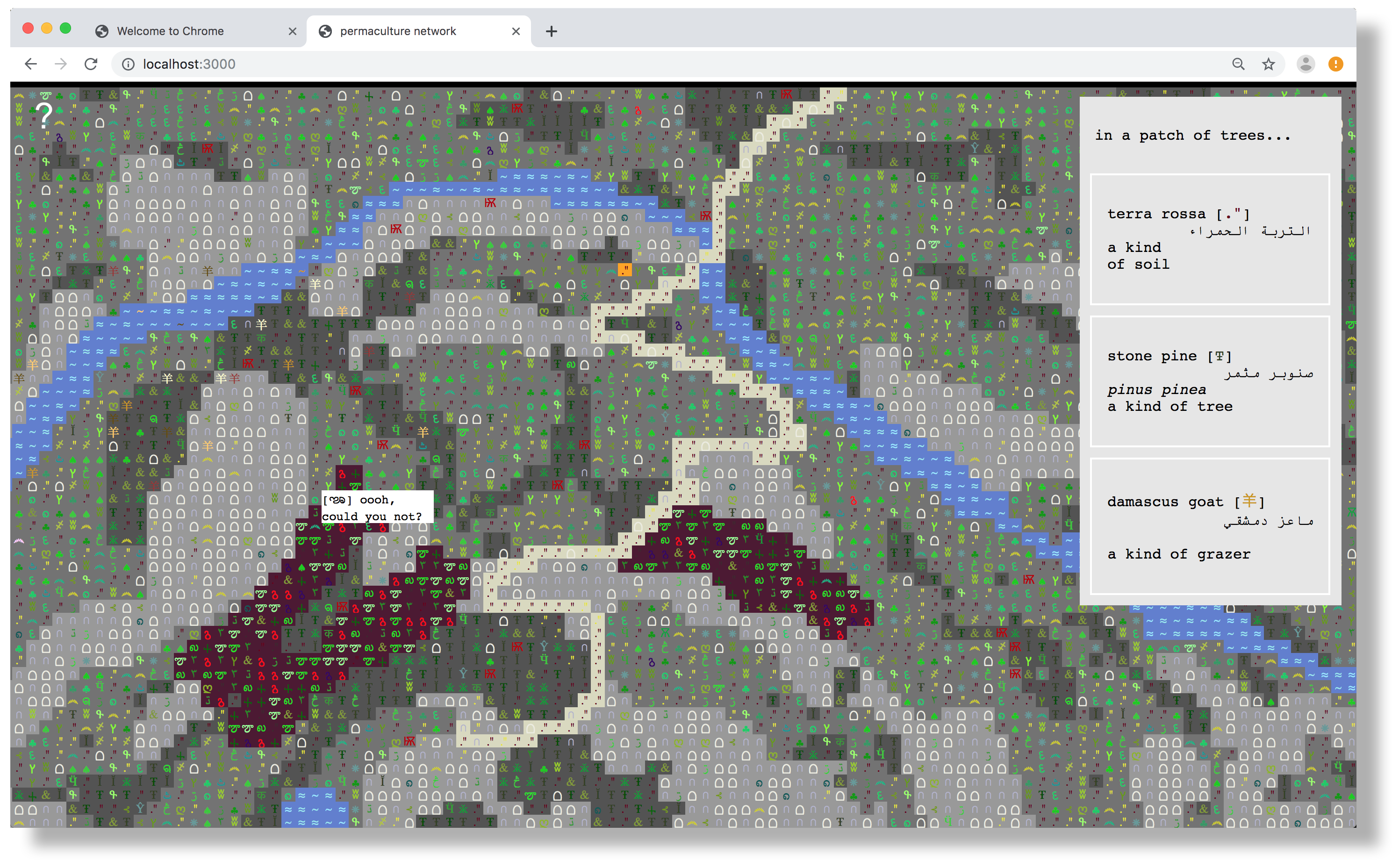

simulation layers

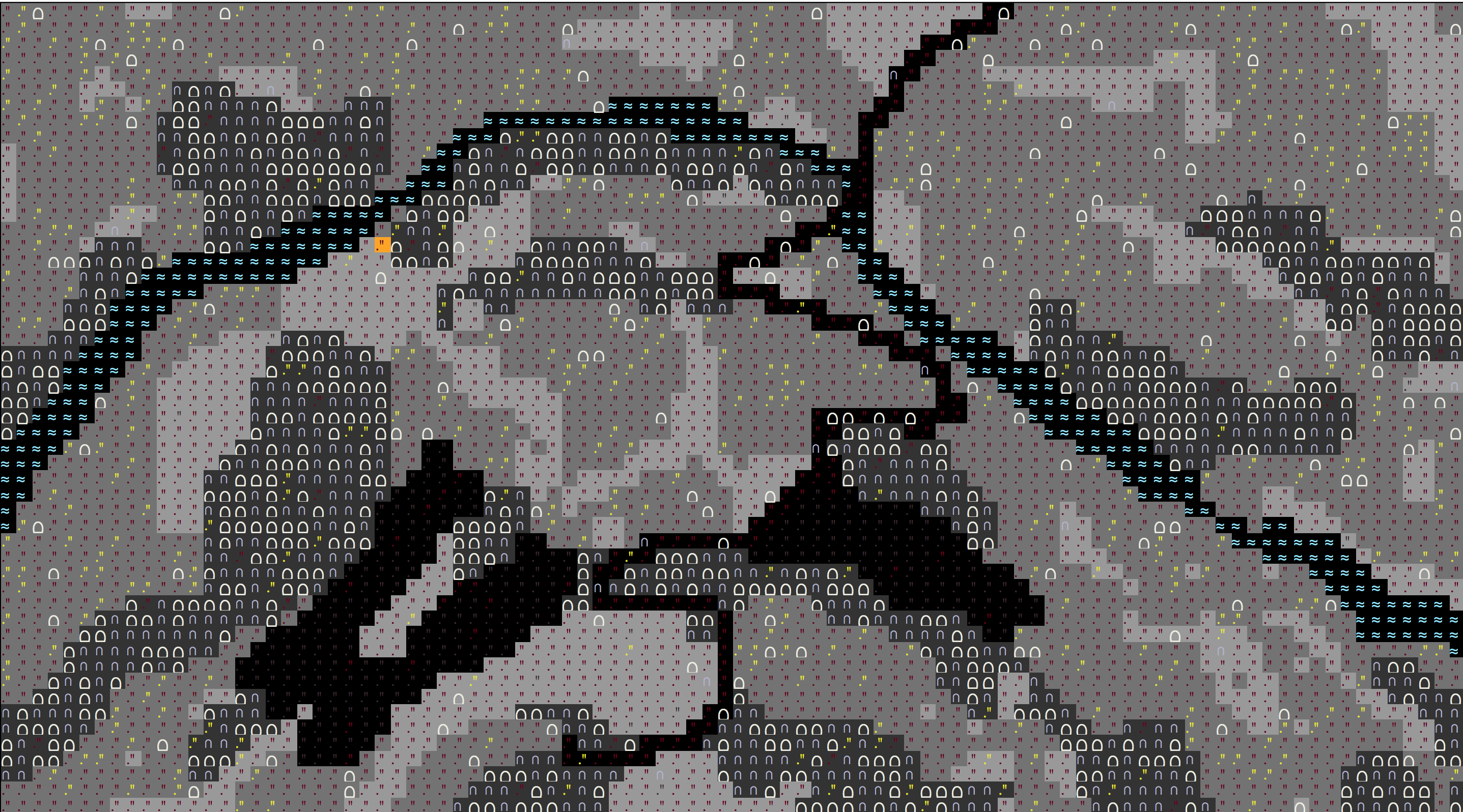

The simulation is built around many ‘layers’ that can co-exist in one of the cells in the simulation grid. The background colours you can see denote the different land types present on the site (you can see this at the top when you click on a square: ‘a rocky outcrop’ ‘a wild meadow’ etc). These types compose the ‘bottom layer’ of the simulation, and are in the same place each time. They are generated from a JSON array which determines the ‘substrate type’ type for each co-ordinate, itself generated from a Python script that takes in a .bmp sketch of how the landscape should look, then outputs a co-ordinate map.

In hindsight, it would have been easy enough to automate this bitmap-generating process by re-writing the python script in Node, allowing the topography of the site to be manipulated much more readily, and to make it easier to adapt to different landscapes.

On top of these substrate types, soils and rocks, then plants, and finally animals, are spawned with a probability that depends on the properties of each land type, and the layers that already exist underneath. These form the ‘layers’ of the simulation. After the initial generation step, nothing moves apart from the animals, though in the future it would be interesting to see plants grow, die and take over one anothers’ cells over a period of time.

the bitmap from which the ‘substrate map’ is created

the bitmap from which the ‘substrate map’ is created

the substrates generated from the co-ordinate map by the simulation

the substrates generated from the co-ordinate map by the simulation

Soil and rocks are distributed according to some probability of walking onto that area and finding that soil. So — in the ‘rocky outcrop’ you mostly get limestone and dolomite, but the ‘wild meadow’ gets terra rossa, and a bit of clay. Plants are then spawned on different soil substrates with a probability according to the kind of soil they like to be on.

![]() tracking where the goats have been during the debugging phase

tracking where the goats have been during the debugging phase

Animals are restricted to the kinds of places you tend to find them: the humans mostly hang out on the path or the terraces, while the goats get everywhere. Herding the goats proved somewhat challenging (as in real life): eventually we settled on having them move slowly downhill and out of shot. Perhaps corralling them around the spring and then dispersing them again would have been more realistic.

cells

The aesthetic of the simulation borrows heavily from dwarf fortress, using ascii characters to represent different entities in the game. Whatever you see is the entity on the top layer of that cell at any given time, though if you click it brings up everything that’s there.

For the animals and humans, we used the chinese characters, because of their pictograhpic appearence, largely due to ‘羊’ (goats).

entities

Entities in the game (plants, animals, soils), are all defined in a set of large JSON arrays, which store their properties: one of plants, one of animals + humans, one of soil/rock types. One of the restrictions we had was that Schloss-Post only gives its residents static hosting, though in hindsight we should probably just have paid for our own servers (or auto-generated these locally), and it’s something we’d definitely do for a second iteration.

"goat":{

"name": "damascus goat",

"zones": [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6],

"number": 30,

"arabic": "ماعز دمشقي",

"latin": 'capra aegagrus hircus',

"symbol": '羊',

"shades": ['#ffffcc', '#ffcc66', '#cc9900'],

"personality": "friendly",

"speech": 'hello hello',

"type": "grazer"

},

The plants have some probabilty of appearing on each substrate type, and also on each rock, based on the kind of environments they’re found in, and the soil they like to grow on. These then get fed into a constructor, which makes a new entity for each square, along with space for thoughts and companions to be created as the simulation progresses.

the simulation loop

the goats (and goatherders) under the ancient oak tree

the goats (and goatherders) under the ancient oak tree

one of the site’s cats, Antar (عنترة), named for the legendary knight Antar Ibn-Shabbad

one of the site’s cats, Antar (عنترة), named for the legendary knight Antar Ibn-Shabbad

The simulation clocked on a single cycle that updates every second. Every time it loops a few things happen.

-

every creature in the simulation (bees, goats, boars, people etc) move, if they want to. Most things move randomly over the kind of terrain they’re likely to be found in, apart from the goats which flock from one side to another (the site is blessed with a flock of 200 goats that come down the hill a few times a week).

-

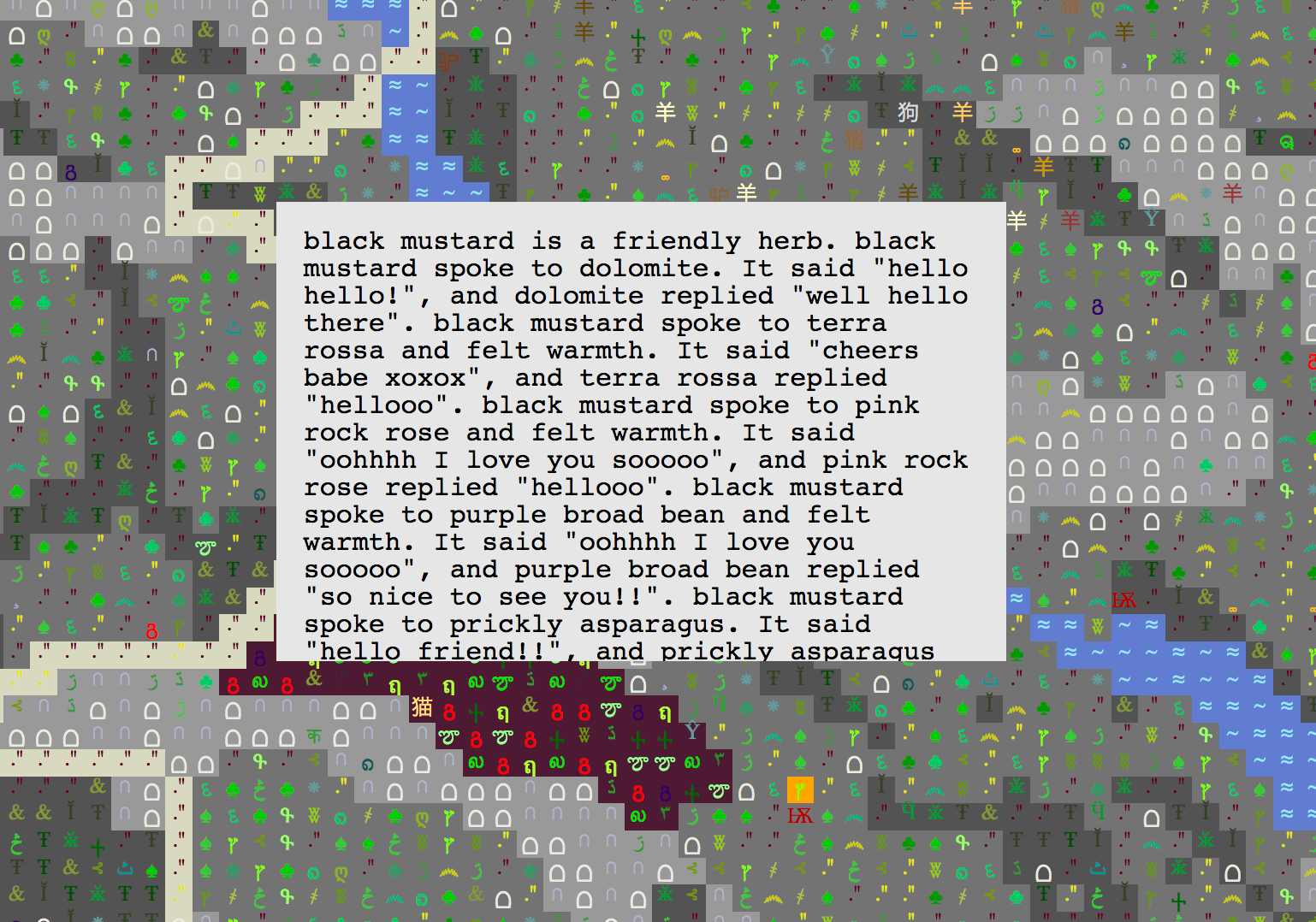

after everyone has moved, the ‘narrative’ aspect of the simulation updates, and conversations are generated first between new neighbours, and 100 agents randomly chosen from the grid

narrative generation

The narrative can be generated in two ways: the first and most direct is when an event occurs — at the moment, that’s just when an animal moves from square to square. When an animal enters a square, this initiates a call-and-response occurs between the animal, and the agent that’s on the top of the square (e.g. if there’s a plant then a plant, otherwise a rock or soil).

The second form of narrative generation happens at random every tick: 100 or so agents are selected, and another agent chosen at random from the 9x9 square surrounding them. If the agent is a plant, and a ‘companion plant’ (in a permaculture guilds sense) is located in this square, then that is chosen with priority. At that point, just as before, an exchange occurs between the randomly selected plant and its neighbour, depending again on personality and relationship. To see the companion plants, you can click on a plant (easiest to do this in the brown ‘terrace’ area as things there are planted in guilds anyway) and the information box should show you the list of nearby companions.

There’s a matrix that maps the kind of interactions different agent types will have with one another: for example, when goats speak to crops or legumes (or really any plant apart from the shrubs, which are spiny and annoying), they will express love and appreciation. This is not reciprocated by the plant (which doesn’t want to be eaten), which will respond with either fear or annoyance, depending on the likelihood of being eaten vs just trodden on.

{

"senderType": "tree",

"receiverType": "amphibian",

"messageType": "curiosity",

},

showing a whole conversation

showing a whole conversation

This matrix, which was just a big JSON object, took a long time to write: with hindsight, it would have been a lot easier to use a database on the backend as a CMS, which I think we’d set up to make this project more modular.

As well as this matrix, each agent has a kind of personality (where we could, these are based on islamic folklore about particular plants): so a friendly agent will express warmth or annoyance differently to how a wise agent would.

Each narrative is expressed in the form of an inner monologue: there are thoughts, and then there is speech. This also takes a lot of inspiration from dwarf fortress: the append-only approach to character development. Right now these conversations don’t really go anywhere or change anything: but it would be really cool to have them change some thing in the interaction, to influence the ecological systems they’re seeking to model.

the narrative of black mustard

the narrative of black mustard

class Speech {

constructor(sender, receiver, message, timestamp) {

this.sender = sender;

this.receiver = receiver;

this.message = message;

this.timestamp = timestamp;

}

}

class Thought {

constructor(thinker, thought, timestamp) {

this.thinker = thinker;

this.thought = thought;

this.timestamp = timestamp;

}

}

In each case, each entity remembers all the converasations it’s had, and also all the thoughts, which get strung together in a narrative.

Additionally, every 10 seconds, the last ‘thought’ or ‘speech’ to be appended to a random agent is printed to the screen. In an earlier prototype, it would also print all the surrounding conversations, but the display was a bit hit-and-miss: sometimes it worked really well, sometimes all the blocks overlapped, and just looked quite confusing.

seasons

One thing we did was to include the flowering seasons of each plant, so that they would change colour over different months. It was a feature we’d basically forgotten about, then we looked back in April and the whole site had transformed. It was a really wonderful feeling: a slow change you’ve completely forgotten about.

everything flowering in April

everything flowering in April

by August, everything's back to plain old green

by August, everything's back to plain old green

future work

There’s a lot of bits that could be done to this, and it feels like the most essential ideas are probably completing work on the site (though that feels pretty far off right now), and adding in a back end that could handle all of the information we’re currently storing in files.

integrating other data

lovely weather we’re having

lovely weather we’re having

One thing we’d been thinking about was to use local weather data to change the state of the simulation: thinking about a game I love by Julian Glander called like Lovely Weather We’re Having, which uses the weather forecast in your location to modulate your experience of the game.

function checkPlantComfort(cell, temperature) {

var tempLevel = getTempLevel(temperature)

switch (cell.plant.preferredTemp) {

case("hot"):

if(tempLevel === "warm")

cell.plant.temperament += 0.2

else if(tempLevel === "med")

cell.plant.temperament -= 0.1

else cell.plant.temperament -= 0.3

...

One way in which this could work would be to use a ‘temperament’ variable to skew the sentiments od responses and conversations. A plant that was normally effusive might become less chatty if it wasn’t currently experiencing it’s preferred temperature… meanwhile a cool, breezy day could really encourage the goats.

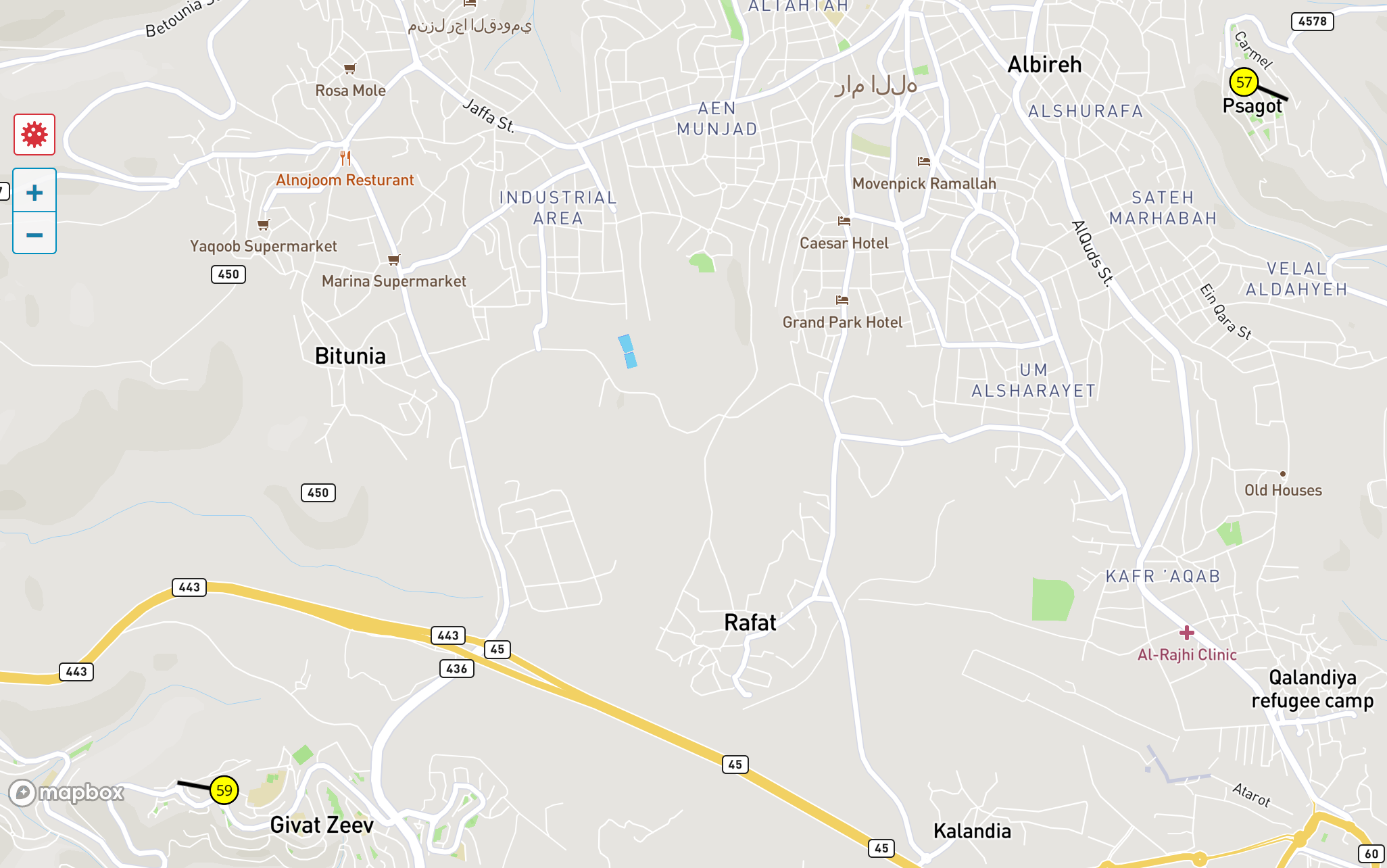

the two nearest weather stations to Ein Qiniyya

the two nearest weather stations to Ein Qiniyya

Initially, we figured that local weather stations could be a good way to use existing data to model this part of the simulation. However, the location of these weather stations makes the use of this data fraught: in the case of Ein Qiniyya, by looking at station data from weather underground, the nearest stations are in Givat Ze’ev and Psagot, both illegal settlements.

It’s both inevitable and frustrating that this is the case: after all, it’s extremely difficult for Palestinians to get access to this kind of equipment, let alone get it on the map and expect to keep it, and it cements the lack of agency they’re able to have over their environment. The work Forensic Architecture did with Public Lab, and the villagers of Al-Araquaib – a guerilla satellite mapping project involving homemade kites to document the destruction of Bedouin villages, and establish a historical continuity for the Bedouin in that area – is a great example of trying get necessary information under the radar. So: no weather for now, perhaps next year!

in other ecosystems

One thing I thought would be really interesting would be to make a simulation based on a different ecosystem and location – or even allow people to build their own!

Everything was made pretty quickly so there’s a couple of bits that would need to be teased out (e.g. the goats have their own function), but for the most part it’s quite modular: all of the animals and plants are defined in separate JSON objects, and the background gets made independently too. What I can imagine being nice is some kind of CMS that would allow you to upload information about your local landscape and populate the sim over time.

The other thing we could do with a backend is to have everyone watch the same simulation every day, as opposed to seeing a new one every time you load the page. This would be particularly nice if we could tie things like the light levels to Sakiya’s time zone.