soft bread, hard times

Last April, Gary and I gave a talk titled “Soft Bread, Hard Times” as part of Akademie Schloss Solitude’s festival Fragile Solidarity, Fragile Connections. The talk (+ accompanying workshop) explored the history and theory of modifying food texture, processes that exist simultaneously on the highly industrial and the intimiate/bodily level. The original slides from the talk are here; this post will likely stray a bit from that order.

staring at starches

staring at starches

I first got interested in texture after reading volumes 1 and 2 of Woodhead Publishing’s Modifying Food Texture, a manual on the science of industrial food processing. I’d ended up there for a project looking at food ontologies, which I plan to write more about soon. On a purely aesthetic level, there’s something deeply compelling about the manuals – a strange tenderness to discussions of how to manipulate the molecular structure of various foods such that they’re experienced as creamier, softer, crunchier or stickier by the person eating them. I’m also interested in the role that the food industry plays in the creation of ‘cheap foods’ – there’s a great short essay by Max Walker on the intertwined history of cheap food, the British Empire, and contemporary free trade – and the use of these techniques into rendering certain crops (like corn, and wheat before it) from ‘foods’ to something more resembling chemical feedstocks.

I maintain a collection of links here relating to industrial food processing, including the manuals I reference here (libgen turns out to be fantastic for leaked industry textbooks, who knew).

What is food texture?

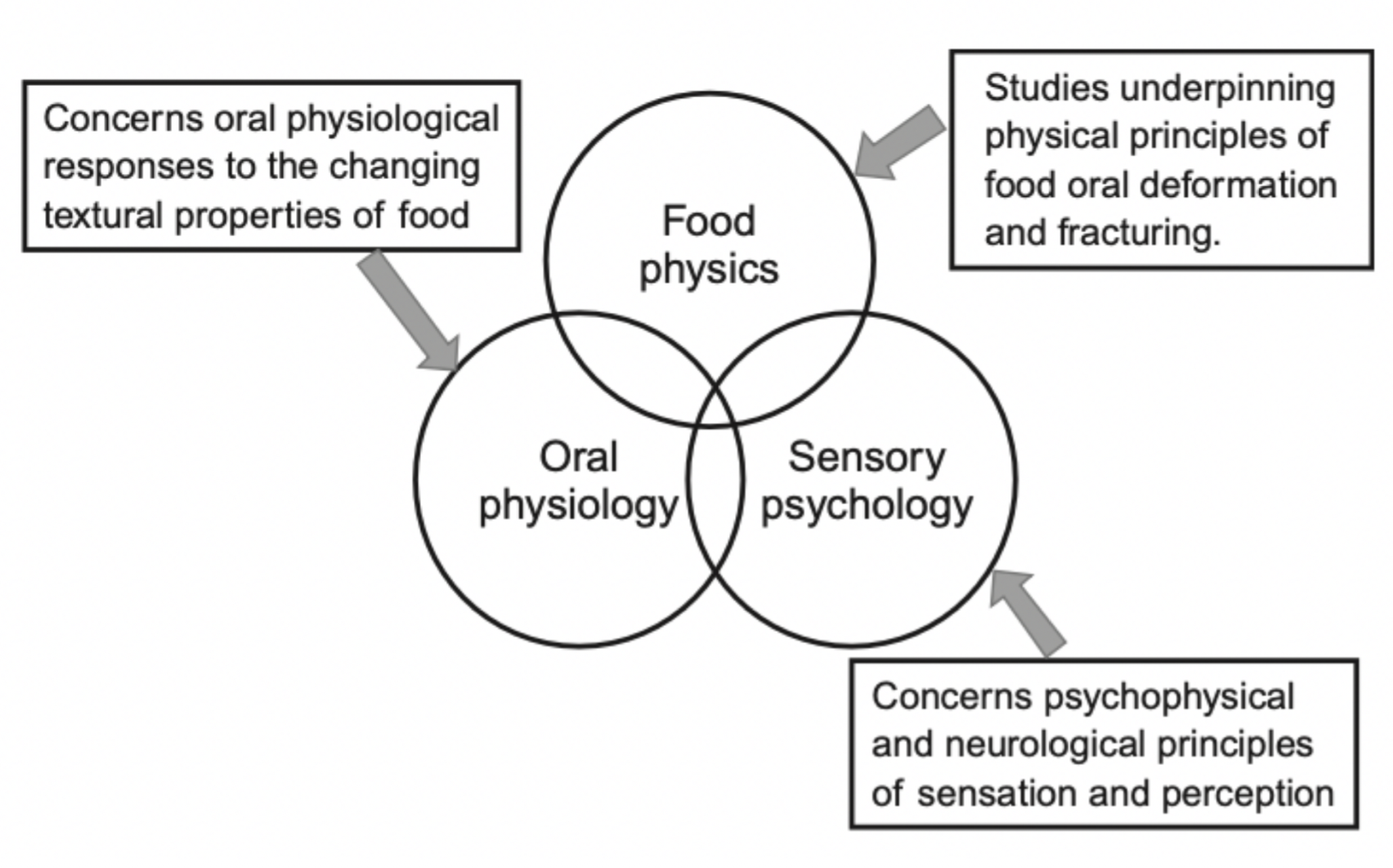

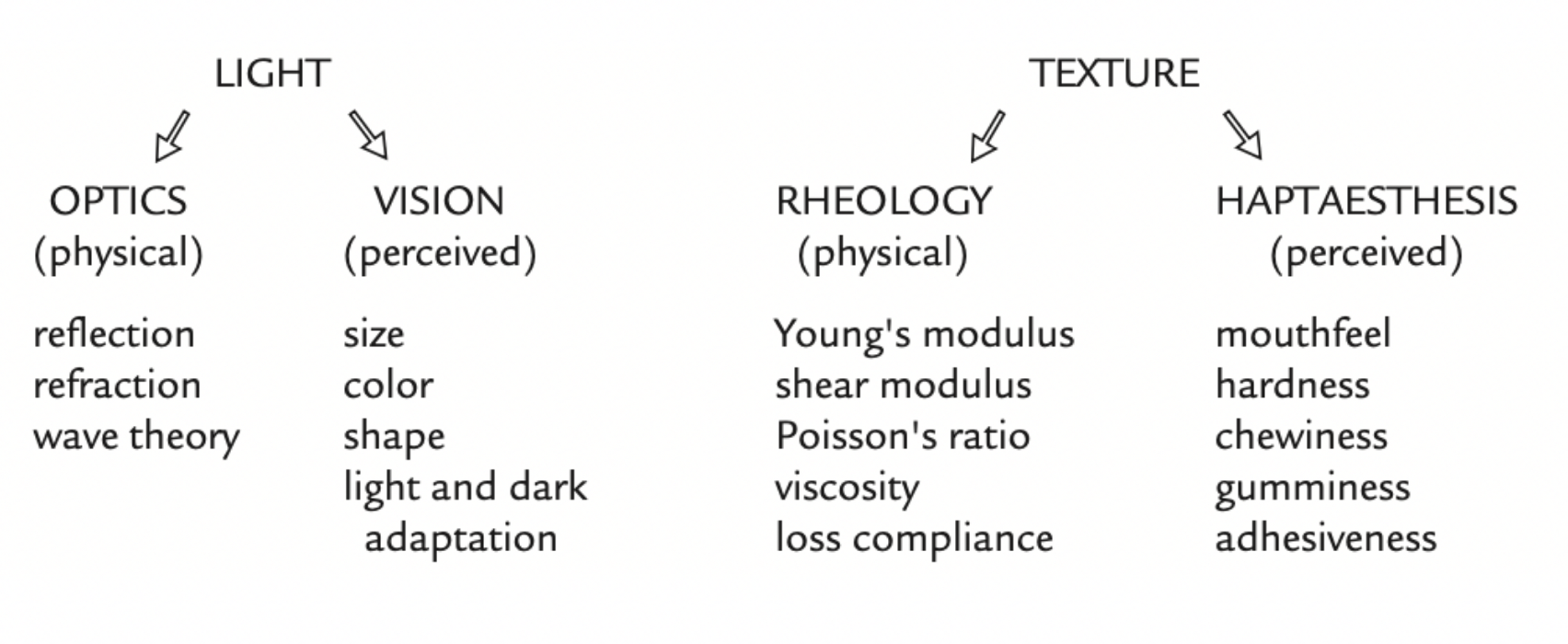

Part of the reason I find ‘texture’ appealing as an area of food science is that it’s a concept that can only exist in relation to human subjective tastes. Specifically, the study of texture sits somewhere at the confluence of sensory perception, the physiology of the mouth, and food physics, most of which falls within the science of rheology – the physics of the deformation and flow of solid and liquid materials. While not all foods ‘flow’ when on the plate, it’s important to remember that the study of food texture is almost entirely concerned with what happens to food in the mouth – and in order for something to be swallowed, even if it didn’t flow initially, it definitely will by the time it travels down your oesophagus.

Eugene C. Bingham – the physicist that coined the term rheology and who is widely regarded as the father of the field – declared in 1930 that:

“The flow of matter is still not understood and since it is not mysterious like electricity, it does not attract the attention of the curious. The properties are ill defined and they are imperfectly measured if at all, and they are in no way organized into a systematic body of knowledge which can be called a science.”

While the study of rheology has come on a great deal since then, there’s still a strongly un-glamorous slant that comes through in a lot of food science writing.

Chemistry vs reality

One of the things that I found quite surprising when I started reading food processing manuals was how humbled all of the authors were by the whiles of human perception. In every book I read, as far as food product development goes, everything came second to how the foods were actually percieved by human tasting panels.

In Malcom Bourne’s Food Texture and Viscosity: Concept and Measurement (a great and comprehensive intro to the field), he bemoans a hubristic fellow chemist running his mouth about how easy it should be for a polymer chemist to synthesise fake meats:

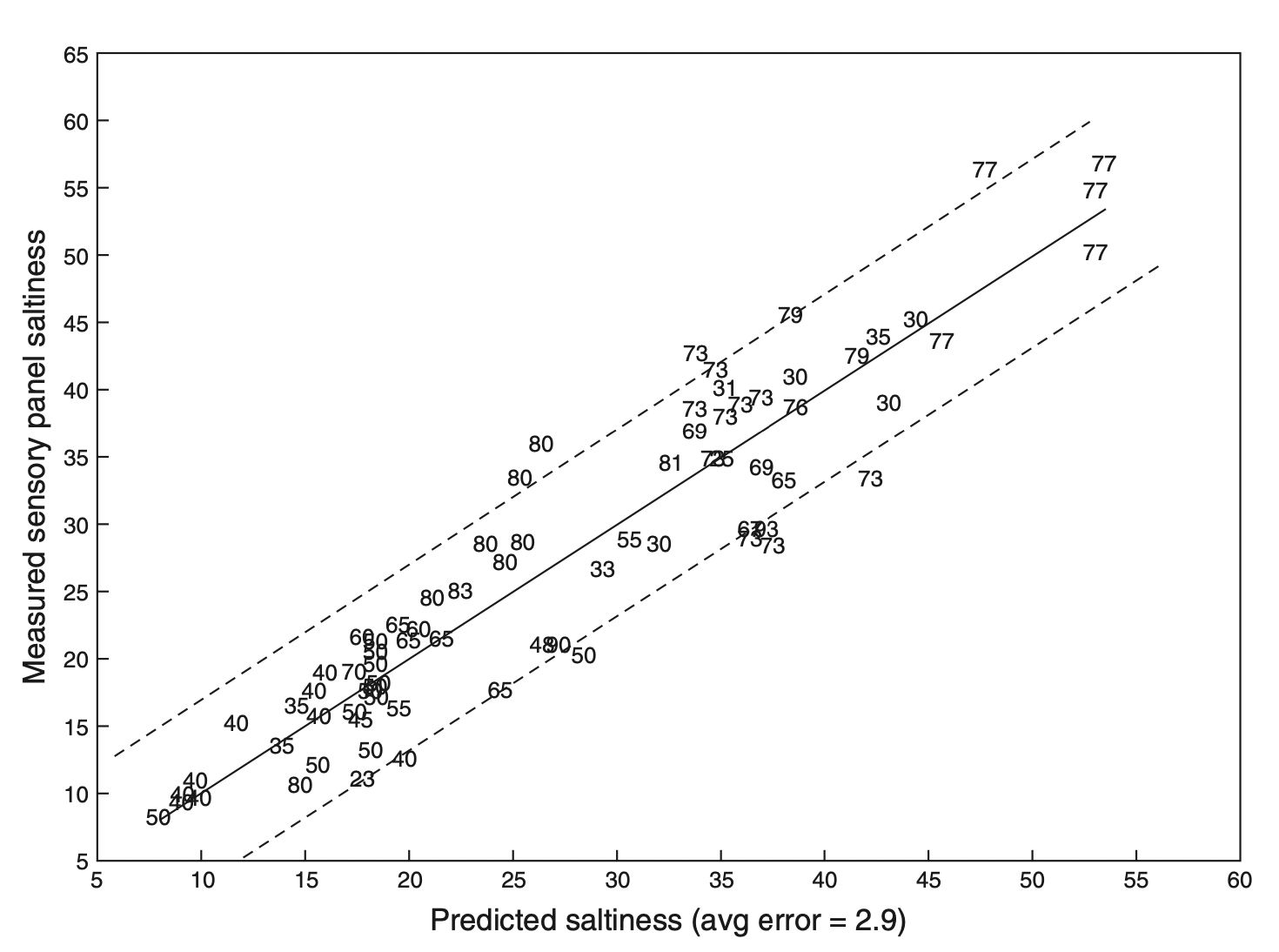

actually percieved saltiness, vs perception of saltiness predicted by the model (as a function of acid/sugar/ salt/oil level plus viscosity, critical strain and amylase thinning), from the Unilever mayonnaise study

actually percieved saltiness, vs perception of saltiness predicted by the model (as a function of acid/sugar/ salt/oil level plus viscosity, critical strain and amylase thinning), from the Unilever mayonnaise study

This scientist should be sentenced to spend 10 years hard labor in the product development laboratory for making such a misleading statement! Acceptable texture has been a limiting factor in the development of many fabricated foods.”

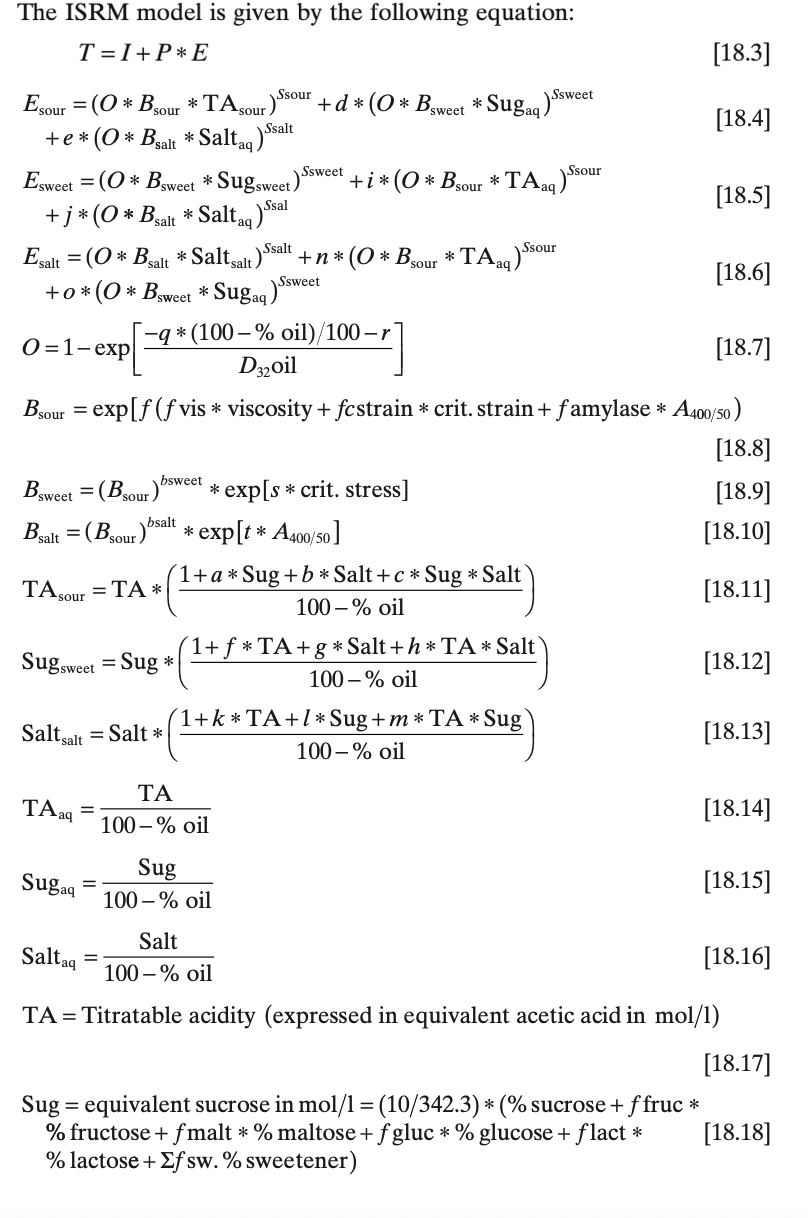

system of equations for the Unilever mayonnaise model

system of equations for the Unilever mayonnaise model

Attempts to close this ‘reality gap’ for various foods are also somewhat astounding in their scale – until you realise that, actually, mayonnaise really is a multibillion-dollar industry, and a ‘Standard Model’ for its perception is probably quite valuable. Hence a really fascinating chapter in the book “Designing Functional Foods”, entitled “Design of foods for the optimal delivery of basic tastes”, which discusses a techique used by a team of scientiasts at Unilever called “Integrated Sensory Response Modelling”, which used a large comparative tasting study of 76 (!) mayonnaises and 192 (!!!) pourable dressings that sought to model the effects of tastants, microstructures, oral processing, and interactions between textures and tastes (caused by things like thickeners) on the taste perception of these products.

Describing Food Texture

Discussion of food texture also comes with its own sets of terminology, for which there are a range of possible ontologies, all of which are geared toward an articulation which can be best married to the creation of a physical model, again desparately trying to make up the space between physics and sensory description.

A chart from Bourne, comparing the physics and perception of light to that of texture

A chart from Bourne, comparing the physics and perception of light to that of texture

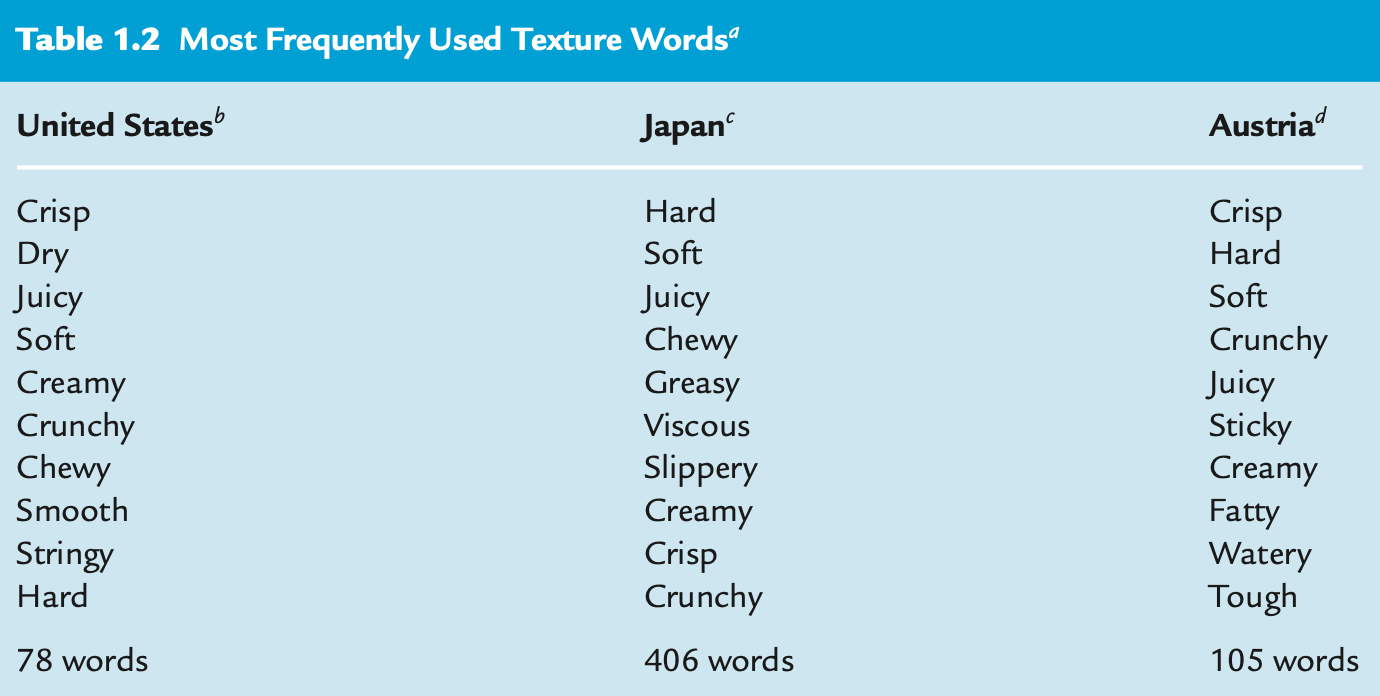

top 10 texture words used by American, Japanese, and Austrian tasting panels, in descending order.

top 10 texture words used by American, Japanese, and Austrian tasting panels, in descending order.

Descriptions of food texture also vary wildly between different languages and cuisines. In a comparison of 3 papers on food texture vocabulary used by tasting panels, Bourne notes that under similar conditions, tasting panels in the US, Japan and Austria came up with 78, 406, and 105 words respectively to describe the texture of foods. While there was a huge disparity in amount, however, six of the top 10 words are common to all 3 lists.

Soft Bread

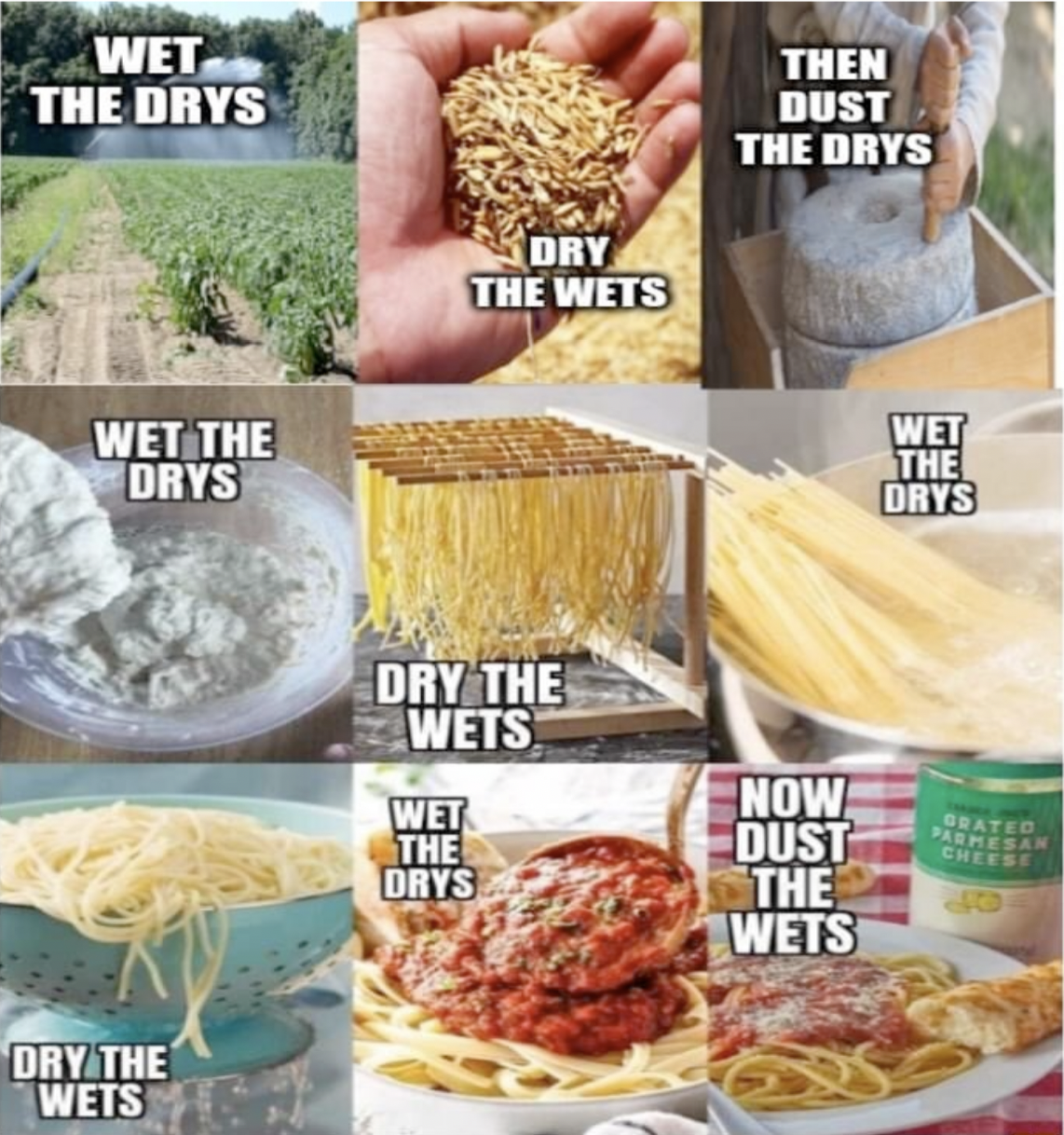

Bourne makes the argument that a great deal of the history of food processing has involved the manupulation of texture:

an accurate meme

an accurate meme

“From the nutritional standpoint wheat could be eaten as whole grains but most people find them too hard to be appealing. Instead, the structure of the wheat kernel is destroyed by grinding it into flour, which is then baked into bread with a completely different texture and structure than the grain of wheat. The texture of leavened bread is much softer and less dense than that of grains of wheat and is a more highly acceptable product, judging by the quantity of bread that is consumed”

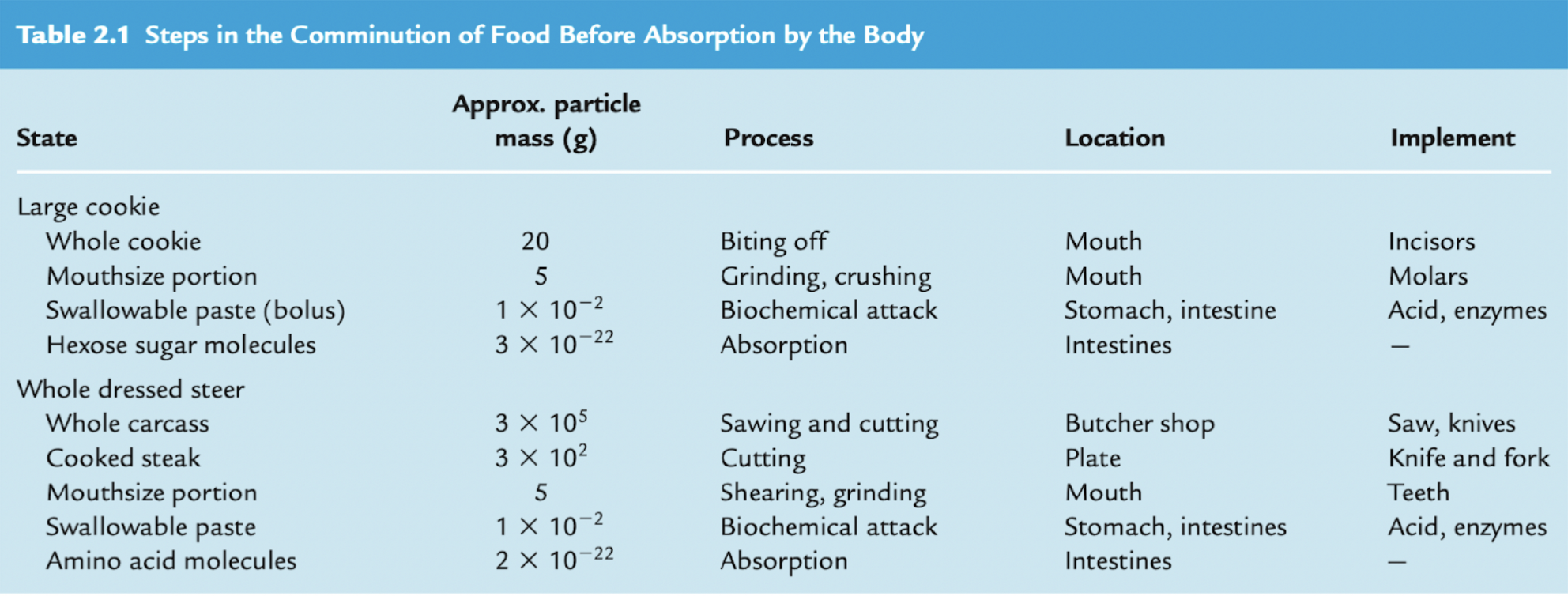

Texture is ultimately an interface to our digestive processes, to the point where many industrial transformations of food mimic digestive processes in our bodies – in particular the use of the enzymes amylase, protease and lipase to break down food into chemical components – in turn making products that are easier to eat and digest. In this sense, texture modification sits somewhere in a chain of processes that end in digestion, but the point where that chain enters the body might differ between processes.

a table from Malcom Bourne's Food Texture and Viscosity, demonstrating the transformation from macro-food to chemical absorption

a table from Malcom Bourne's Food Texture and Viscosity, demonstrating the transformation from macro-food to chemical absorption

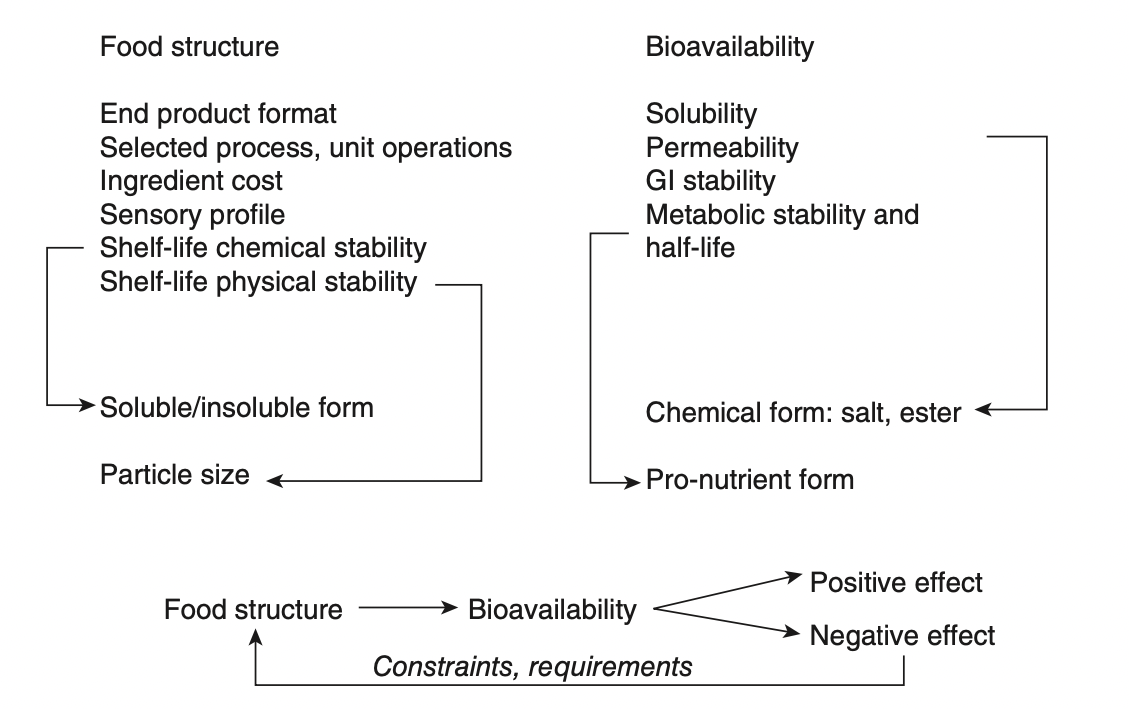

This modification is not just for the purposes of pleasure – the texture (and thus structure) of foods can determine to a great extent the bioavailability of different nutrients in the food – how much of a nutrient can be absorbed, and how. Just as the simple starches in processed white bread are much more rapidly broken down by the digestive system, so the bioavailability of the food has been directly affected by adjustments in the manufacturing process.

Much of the second volume of Modifying Food Texture is concerned with this kind of manipulation, specifically making foods softer such that they might be more easily be consumed by people suffering from dysphagia or difficulty swallowing, a condition associated with a number of different conditions and often experienced by people as they age.

Hard Times

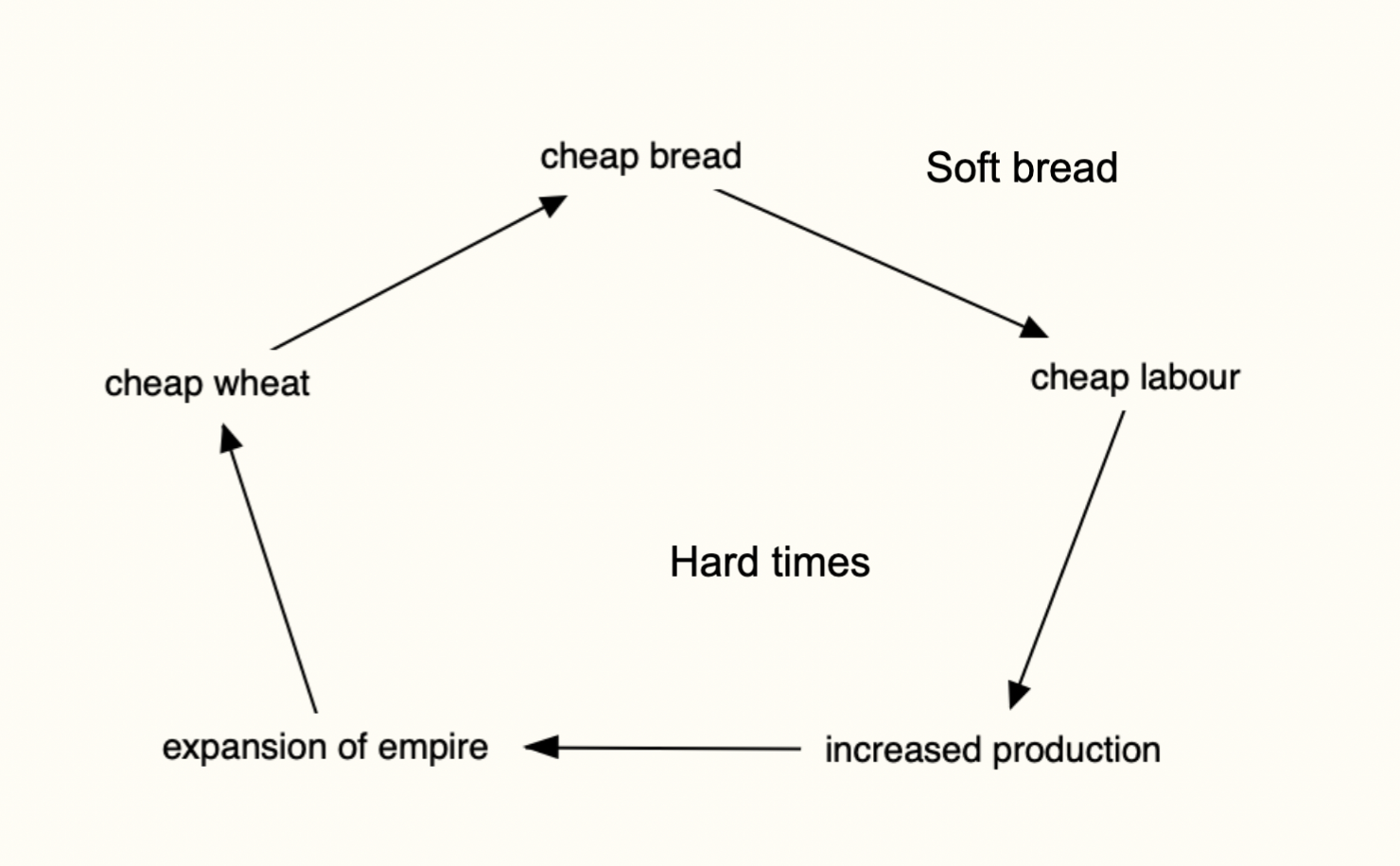

soft bread <-> hard times; an approximate system diagram

soft bread <-> hard times; an approximate system diagram

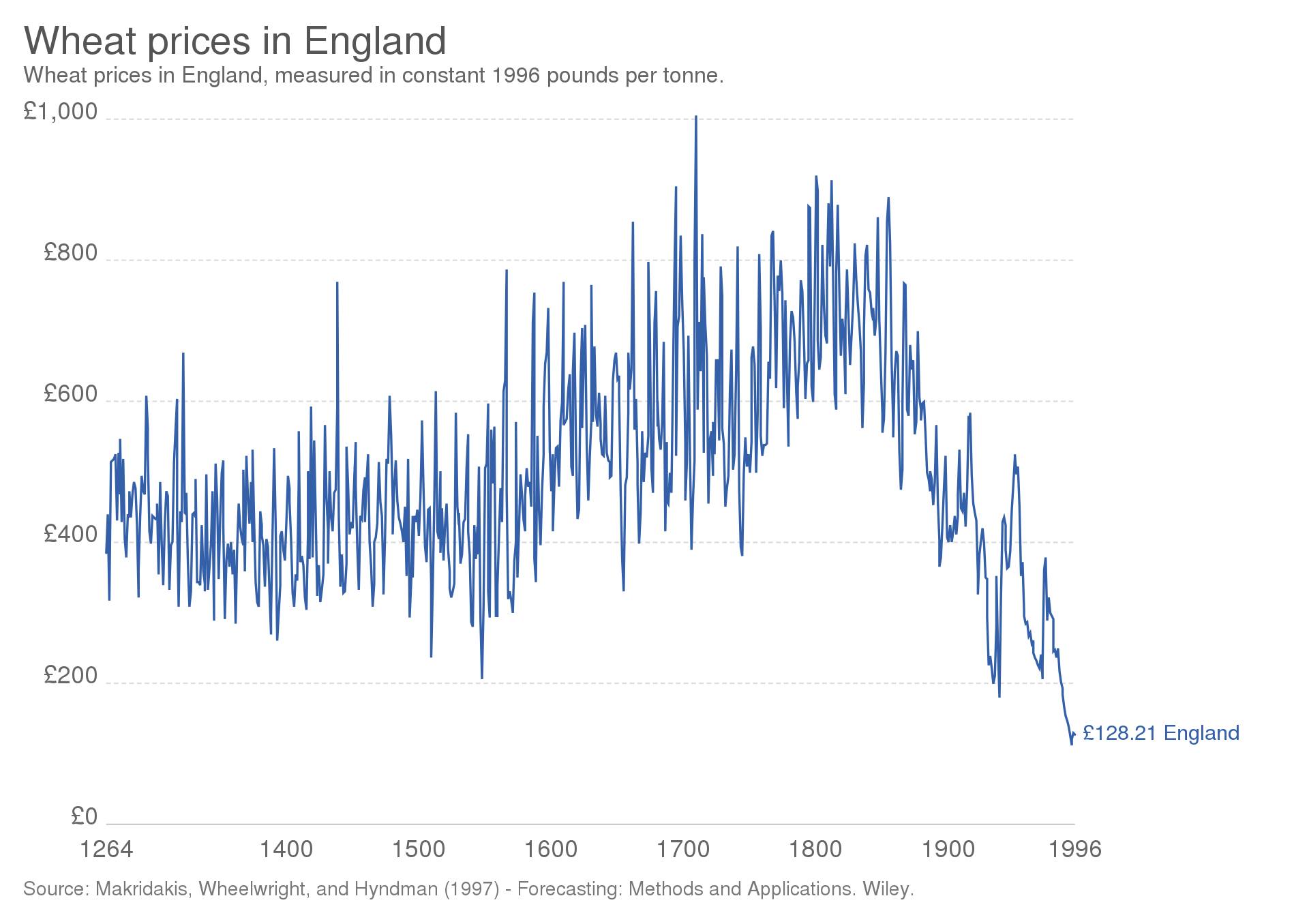

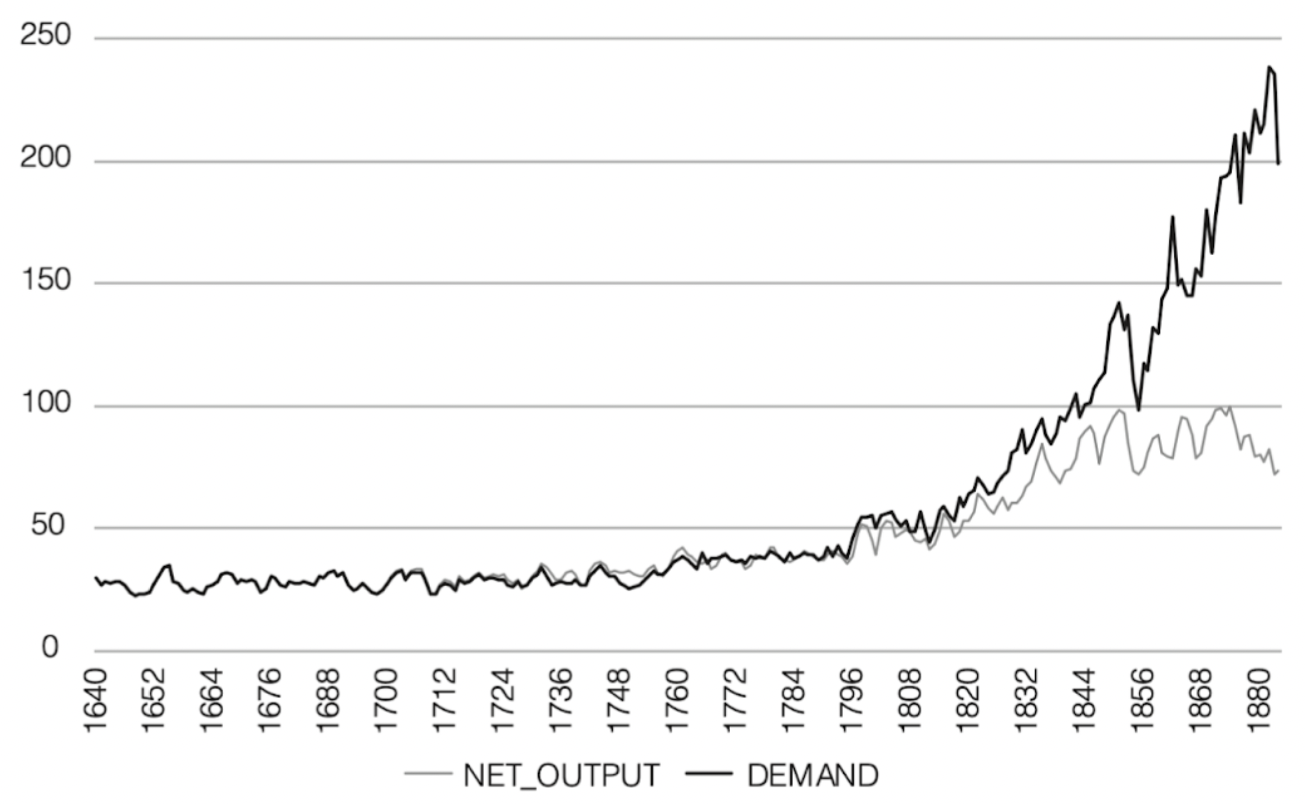

The industrial production of bread has several origin points, though a key turning point in development of contemporary industrial bread manufacture was the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 (followed by abolition of cereal duties in 1869). The Corn Laws were a system of tariffs implemented by the British Government introduced in 1815 that blocked the import of cheap grain (wheat, oats and barley) into the UK. Their repeal saw an influx of cheap grain from North America, and a squeeze on farmers in the UK (who could no longer sell grain), pushing people into a rapidly-growing urban working class, which in turn was used to drive the industrial revolution.

the price/ton of wheat in England, 1264-1996, via Wikipedia

the price/ton of wheat in England, 1264-1996, via Wikipedia

As Jason Moore and Raj Patel argue in A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: “cheap food enables cheap work to yield riches” – the cheap grain (and cheap bread that was produced from it) allowed for the proletarianisation of an urban workforce, whose labour fuelled the industrial revolution and the expansion of empire.

In 1862, 16 years after the Corn Laws were repealed, Dr. John Daugleish founded the Aerated Bread Company, pioneering a no-knead chemical leavening process that allowed for a high degree of automation. The process reduced both the time and labour costs associated with breadmaking, thus markedly reducing the price of bread. When it was introduced to the Australian market, ABC is thought to have pushed down the price of bread locally between 8-17%, according to an article published in the Adelaide Observer.

Daugleish’s process was refined in 1961 into the Chorleywood Bread Process, a high-volume and high-speed industrial bread process which is used to make around 80% of bread in the UK, Australia, New Zealand and India today.

British food policy is still based overwhelmingly on extractive import agreements and export monocultures that hark back to colonial trade policies. In 1863, agricultural chemist Justus von Liebig, talking about the colonial extraction of fertiliser declared In – I am not kidding – Farmer and Gardener Magazine, 1863 edition that:

english wheat demand vs production in millions of bushels, 1640-1880

english wheat demand vs production in millions of bushels, 1640-1880

“Great Britain deprives all countries of the conditions of their fertility. It has raked up the battle-fields of Leipsic (sic), Waterloo and the Crimea; it has consumed the bones of many generations accumulated in the catacombs of Sicily; and now annually destroys the food for a future generation of three million and a half people. Like a vampire it hangs on the breast of Europe, and even the world, sucking its lifeblood without any real necessity or permanent gain for itself.”

Corn is a Platform

If the defining crop of the British Empire was wheat, the equivalent to the American empire would be corn (maize). Cultivated for centuries by indigenous peoples across North, Central and South America, having likely been domesticated in the Mexican highlands and spreading to eastern North America by 900 A.D. The Aztec and Maya used a process called nixtamalisation to process corn by cooking the kernels in an alkaline solution, considerably improving its nutritional value and changing its texture. European settlers did not take up this technique, leading to endemic pellagra in settler populations in the US in the early 20th century

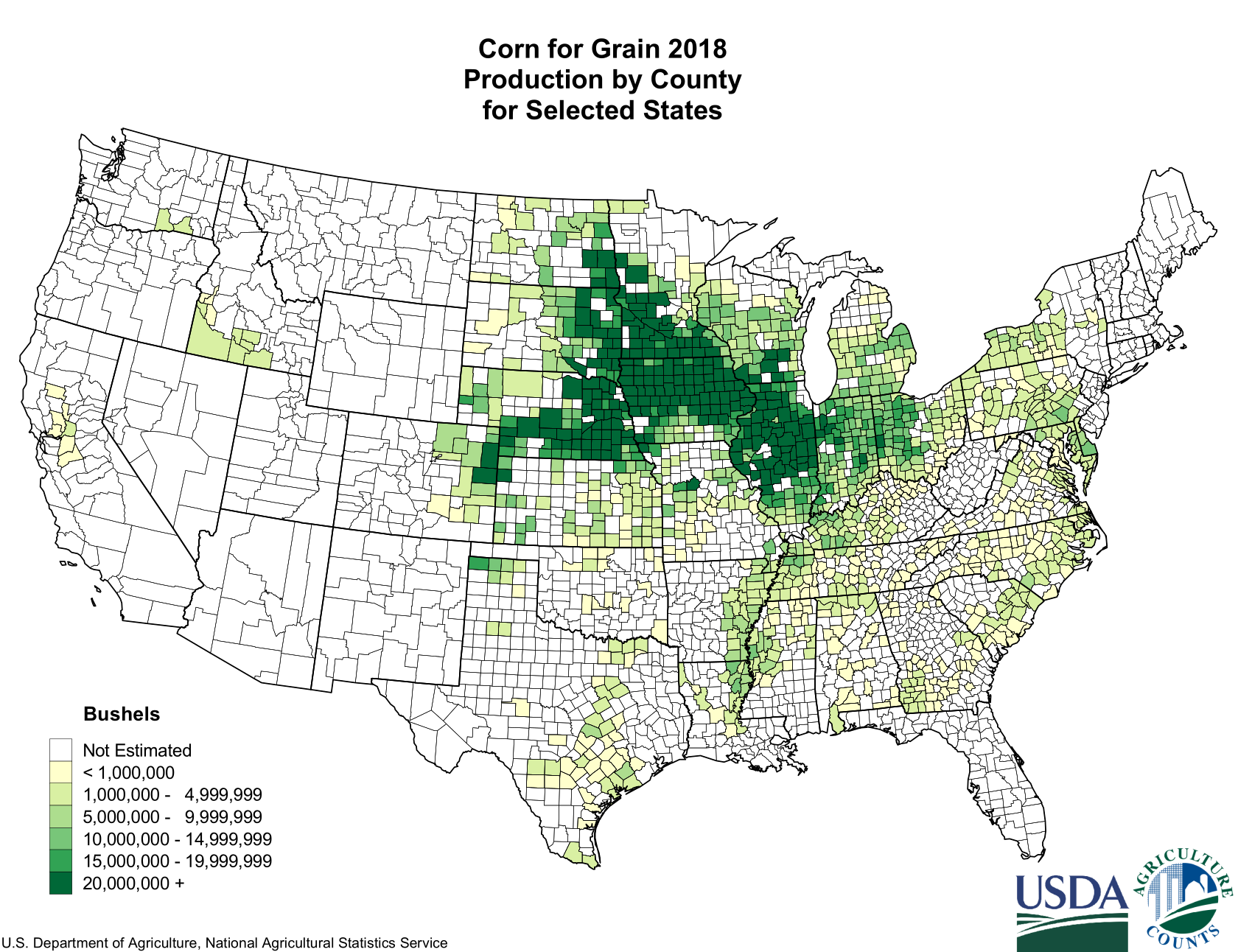

the corn belt

the corn belt

Corn was cultivated by European settlers, who used the growing techniques of indigenous groups to expand corn agriculture across the Midwest (creating the Corn Belt), spurred on at the start of the 20th century by massive corn subsidies. The US is now far and away the world’s largest maize producer, at 360 million tonnes (in 2020) a full 100 million tonnes ahead of the next-most prolific producer, China.

Corn Wet-Milling

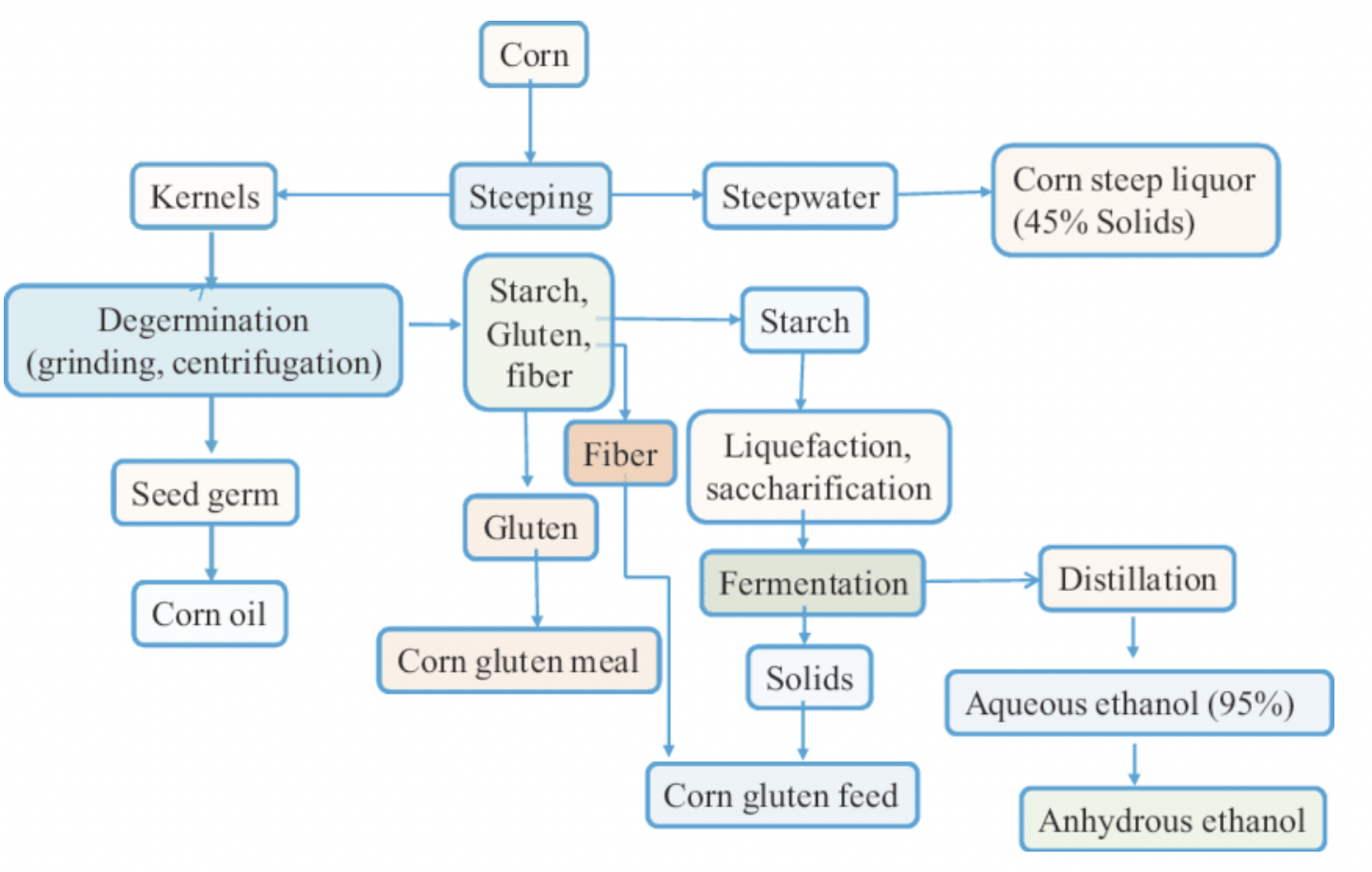

Part of corn’s appeal comes from a process known as wet milling, which processes corn kernels into separated corn oil, starch (which can then be processed into sugar, and then ethanol), gluten meal and fibre, and which has an almost 100% yield (e.g., every part of the process turns into a usable product).

a chart of the products from corn wet-milling

a chart of the products from corn wet-milling

Through this process, corn is not processed into ‘food’, more a list of chemical feedstocks as suited to transform into foods as they are into fuels, plastics or animal feeds. This is a process that suddenly allows you to jump between points in ‘texture-space’, rather than dealing with discrete ingredients.

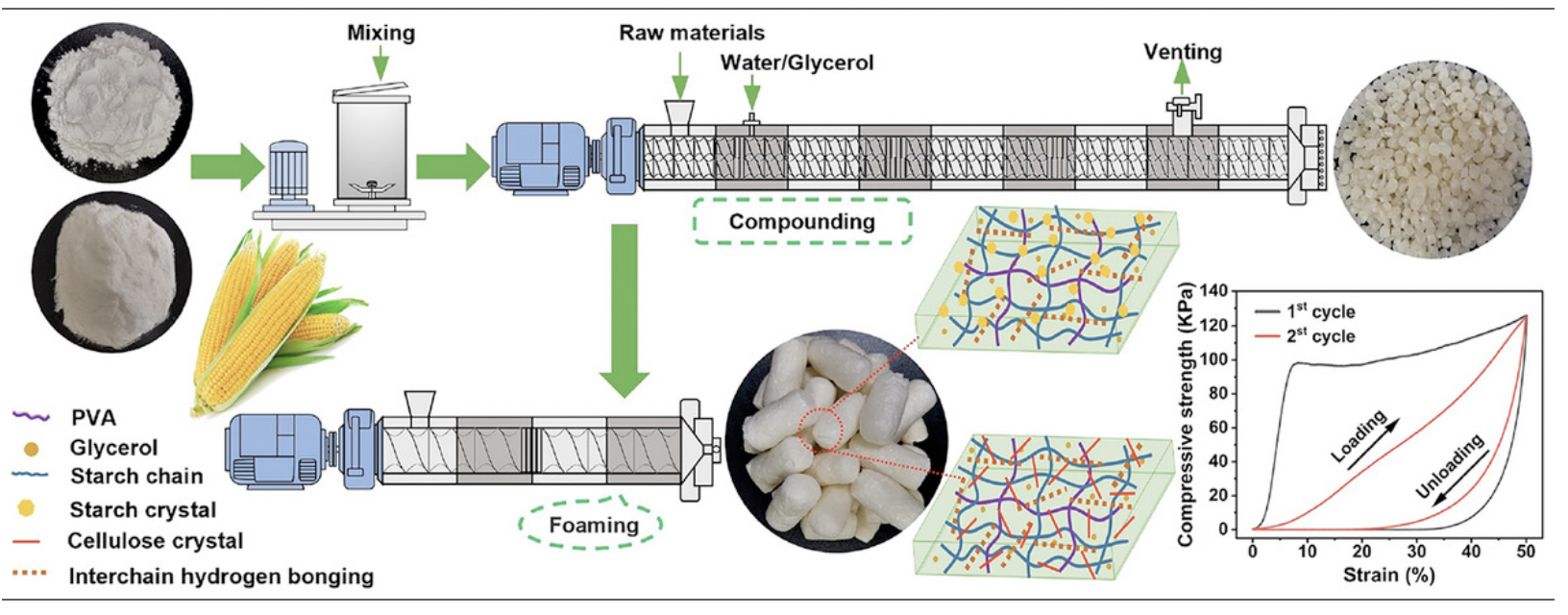

The process for making packing peanuts, for example, strongly resembles the process for making puffed corn snacks like Wotsits, with the added step of sugar removal to prevent the material from being appealing to rats and mice. These pellets are extremely cheap to produce, and through the manipulation of solid foam texture have excellent force-absorbing properties.

a diagram showing packing peanut production

a diagram showing packing peanut production

Grain Research

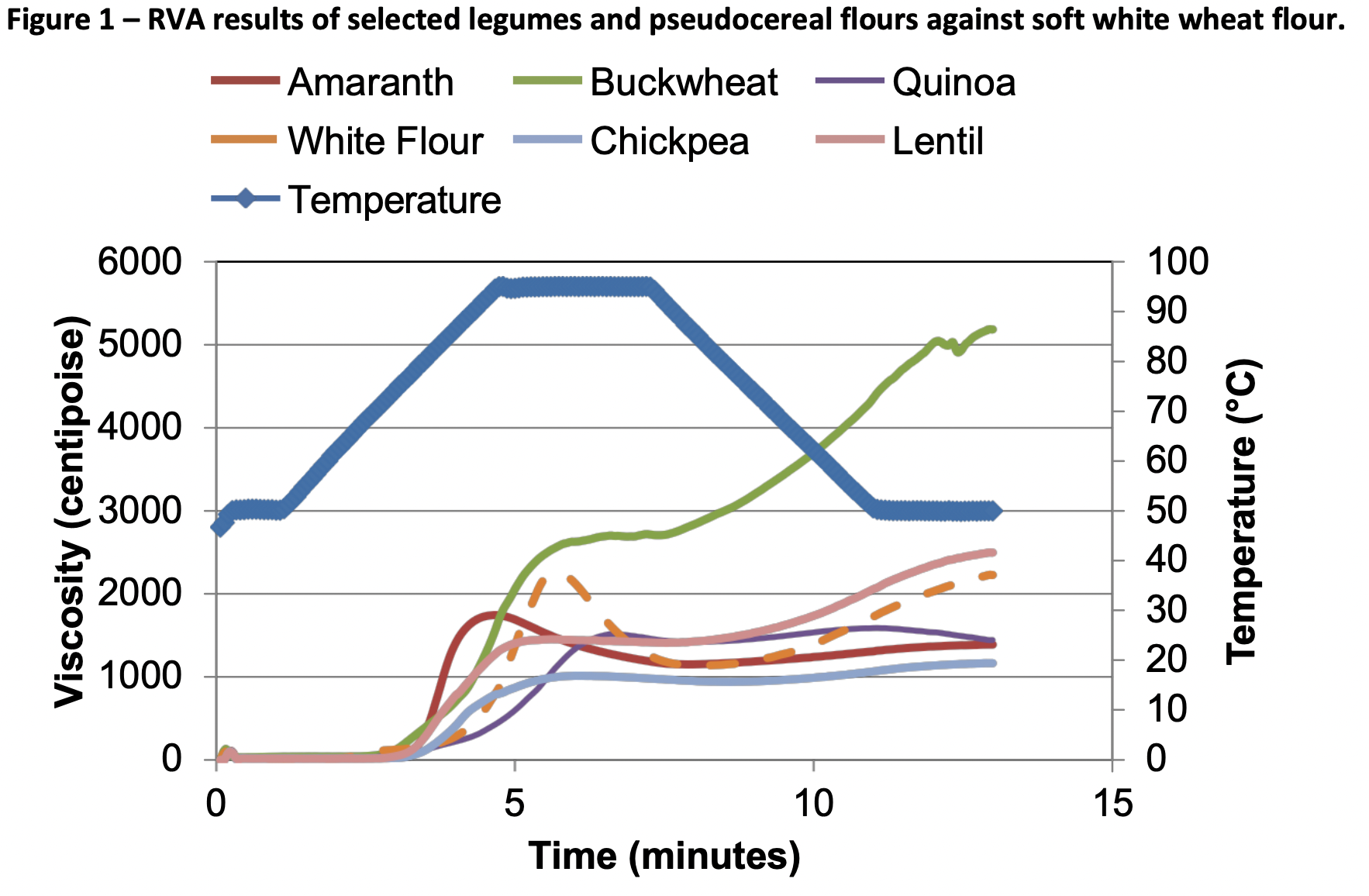

chart showing the change in viscosity over time (when subjected to a temperature curve) of different pseudocereal flours

chart showing the change in viscosity over time (when subjected to a temperature curve) of different pseudocereal flours

Campden BRI, renamed from the Chorleywood research center are still conducting food science research, working as a research consultancy for industrial food procucers. In a recent research paper, Legumes – an alternative to cereals?, McGurk, Sahi and Heuer investigate the use of legumes and the pseudocereals amaranth, quinoa and buckwheat in breadmaking, using the analysis of starch gelatinisation temperatures to propose baking methods that reproduce the texture of wheat-based bread using a disparate range of inputs. In some senses this feels almost like a full circle, the heart of ‘big bread’ finding alternatives to wheat that create the same product… and maybe in other senses it feels like Shell’s renewable energy research division.

Future Textures

Where does all this take us? In the next decades, it feels clear that (simplistically) our relationship to food policy (at least in the UK) needs to transform from a system of colonial extraction based on export monocultures to one focussed on what can be grown locally, without taxing the soil to the point where nothing can be grown at all. In part, this requires us to transform the inputs to the food system we currently inhabit to focus on a more sustainable set of crops. Likewise, there is a need to reduce the amount of meat we consume across the board, and also reduce the amount of land given over to the production of animal feeds and biofuels.

Texture modification gives us a set of industrial tools that allow us to imagine making similar foods with, for example, a much greater diversity of grain varieties while still retaining the ability to make staples such as bread.