agrarianism and revolution reading group

The Agrarianism and Revolution Reading Group met weekly for the duration of the Delfina Foundation’s 2022 Politics of Food Programme. Organised by myself and fellow resident Åsa Sonjasdotter, the impetus for the group came from a shared interest in discussing radical movements, ideas and materials concerning land and food. ARRG (as it is affectionately known) met 10 times over the course of the season, and will continue online on a biweekly basis, probably from February onward.

Each session combined two readings, along with artefacts and materials brought by participants (highlight: Åsa brought flints from Suffolk). We would take turns to read aloud extracts from the text, finding links and parallels between the readings. At the end of each session, we would discuss the direction we next wanted to take, and myself and Åsa would select the next weeks’ extracts. In this way we meandered through a series of texts linked by intention and interest, covering a wide range of ideas and ideologies. At the turning point between seasons, I wanted to write an overview of the ideas we’d talked about, summarising some of our notes from the sessions and looking at the links between our paths of thought. This is not intended to be a thorough overview of all the materials, more of a meandering tour.

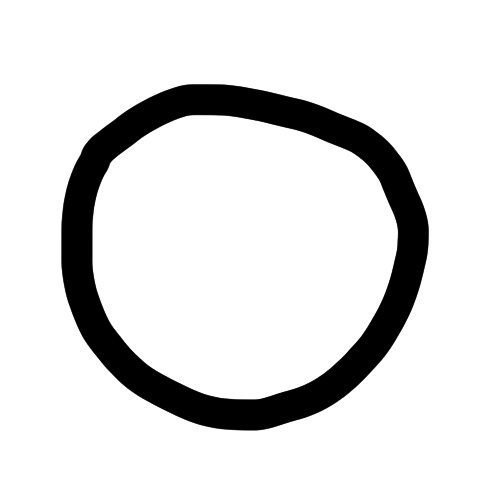

I’ve tried to summarise the path we took through the readings in the diagram below.

start: cabral and meiksins-wood

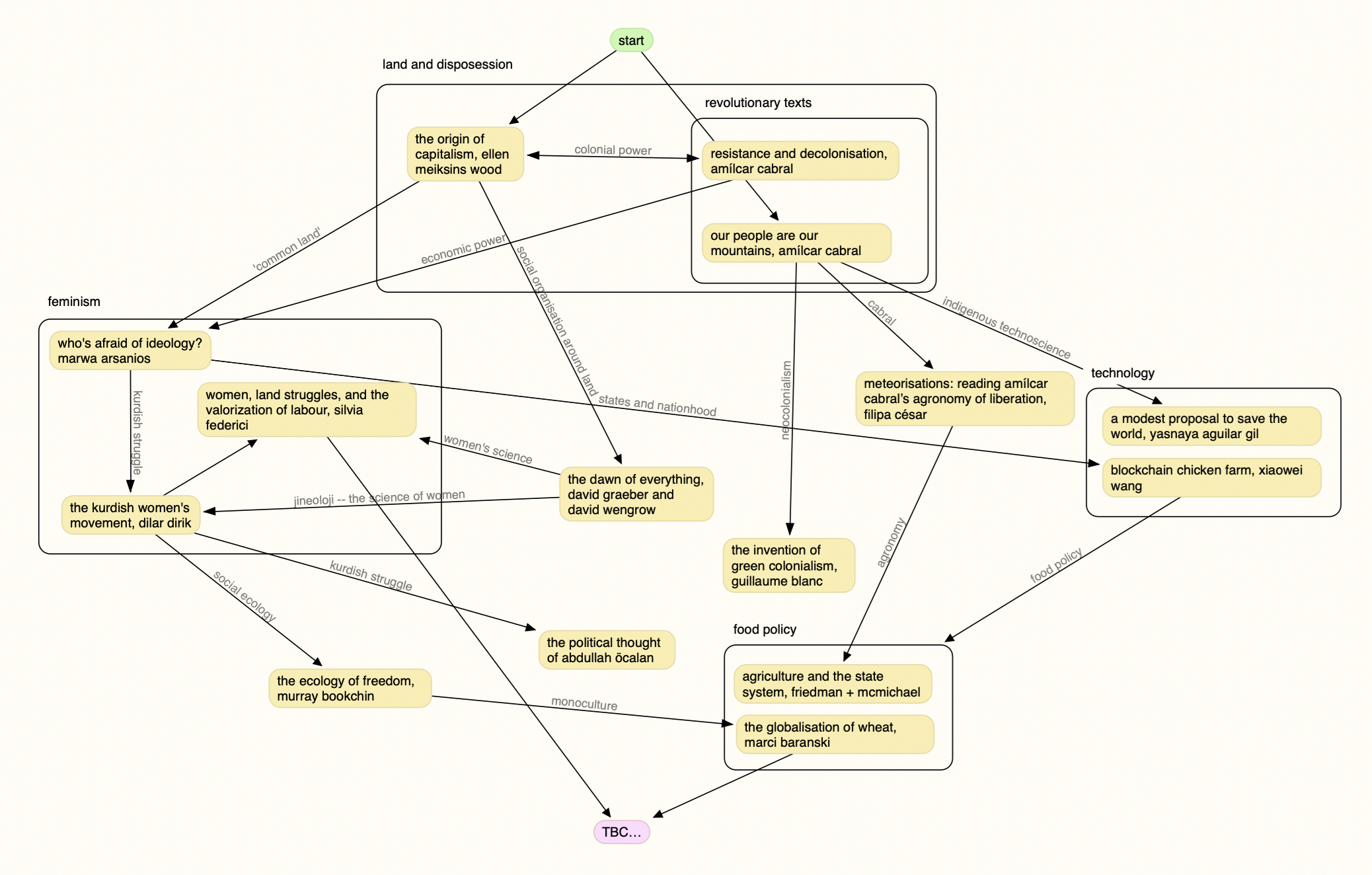

Amílcar Cabral during the Guinean revolution

Amílcar Cabral during the Guinean revolution

We began the season with a pair of readings chosen by myself and Åsa – Amílcar Cabral’s speeches, in Our People are Our Mountains, and Ellen Meiksins Wood’s The Origin of Capitalism, a Longer View. These paired very well, both making interesting arguments about the feedback between social organisation, land use, and domination (colonial or internal). We specifically read the question-and-answer session with Cabral, where he discusses the successes, aims and projects during the height of the Guinéan revolution.

In The Origins of Capitalism, we focussed on two chapters discussing Meiksins-Wood’s theory of capitalism’s origins in English land management in the 15th century. She starts the first of these with a definition of appropriation and economic coercion, as it relates to the land:

For millennia, human beings have provided for their material needs by working the land. And probably for nearly as long as they have engaged in agriculture they have been divided into classes, between those who worked the land and those who appropriated the labour of others. That division between appropriators and producers has taken many forms, but one common characteristic is that the direct producers have typically been peasants. These peasant producers have generally had direct access to the means of their own reproduction and to the land itself. This has meant that when their surplus labour has been appropriated by exploiters, it has been done by what Marx called ‘extra-economic’ means - that is, by means of direct coercion, exercised by landlords or states employing their superior force, their privileged access to military, judicial, and political power.

The argument she goes on to make is quite detailed, but begins with the assertion that capitalist relations in England did not begin with the land enclosures but rather enclosures were the endpoint of a much longer process of dispossession of the peasantry. Increases in agricultural productivity are linked to the transformation of land relations from the feudal tithe system to a system of competitive rents, where farmers leased land from the lord and thus needed to maximise profits. Only in capitalism, the dominant mode of appropriation is based not on direct coercion, but on the complete dispossession of direct producers, who need to sell their labour on the capitalist ‘market’.

This unique set of social arrangements, she argues, could happen in England because of the comparatively coherent transport + trade networks throughout England, themselves a result of colonial domination by the French, and are what allowed for later developments, such as the Industrial Revolution.

Cabral’s discussion of land relations in Guiné gives us some interesting parallels:

Naturally, people in Europe expect ‘agrarian reform’ in my country. But in Guiné (Cape Verde is a different matter) the problem of agrarian reform is not the same as it is in Europe. This is because the land is not privately-owned in Guiné. The Portuguese did not occupy our land as settlers, as, for example, they did in Angola. The Africans kept the land and the Portuguese appropriated the results of his labour. As a result, most of the land has remained the property of the villages. Of course, in tribes like the Fula or Mandjak, which have a pyrami- dal social structure, the chiefs have the best land. But they have it only in terms of getting the best possible production from it; they do not own it, for it cannot be sold or otherwise disposed of.

We do not therefore have the problem of agrarian reform in relation to land ownership that other countries are familiar with. What we need is an agrarian revolution to improve the yield of the soil through technology, and we believe that the best structure for this change will be a co-operative system. …We believe that we must develop the co-operative as the fundamental economic structure in our way of life, not only internally as the basis of our whole economy but also in terms of our country’s international economic relations.

link: social organisation around land

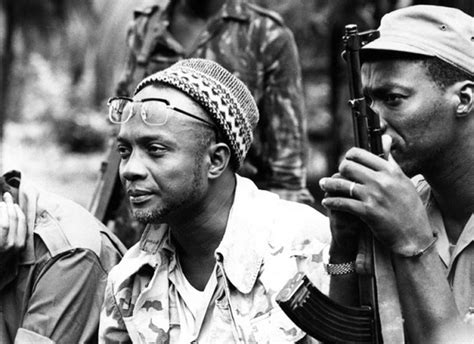

three-field crop rotation system, introduced in Europe between 9th-11th century

three-field crop rotation system, introduced in Europe between 9th-11th century

Inspired in particular by Meiksins-Wood’s analysis, and also by Cabral’s discussion of economics in Resistance and Decolonisation, we started to read extracts from David Graeber and David Wengrow’s book The Dawn of Everything, which traces back agricultural histories to the Neolithic era. In particular, the discussion stemmed from ideas about how social relations shape and are shaped by the relationship to the land, and agricultural relations in particular.

One of the most compelling and powerful arguments made in the extract we read was the consideration of the first ‘agricultural revolution’ (the 3000-odd year period where crops moved in and out of domestication) as at its heart an informational and scientific revolution, as technologies of textiles and image-making were developed alongside the development of agricultural practice.

Seen this way, the ‘origins of farming’ start to look less like an economic transition and more like a media revolution, which was also a social revolution, encompassing everything from horticulture to architecture, mathematics to thermodynamics, and from religion to the remodelling of gender roles. And while we can’t know exactly who was doing what in this brave new world, it’s abundantly clear that women’s work and knowledge were central to its creation; that the whole process was a fairly leisurely, even playful one, not forced by any environmental catastrophe or demographic tipping point and unmarked by major violent conflict.

link: the science of women

Graeber and Wengrow’s argument about the agricultural revolution also dubs it a science of the concrete, a term coined by Lévi-Strauss which refers to a science rooted in material practice. They argue that women were at the centre of this kind of innovation, but are rarely credited as such.

These assertions share a lot of ground (with good reason – Graeber was heavily influenced by the Kurdish movement and supported them throughout his career) with the notion of jineolojî, or womens’ science, an ecofeminist ideology rooted in the Kurdish independence movement.

Along this line, we chose readings from the artist and writer Marwa Arsanios and member of the Kurdish women’s movement and scholar Dilar Dirik, both of whom write on feminist revolutionary land struggles and agriculture in the Middle East, with Dirik writing specifically from the Kurdish perspective. In her piece Who’s Afraid of Ideology?, Arsanios actually interviews Dirik, and the links between the two are very strong.

Arsanios’ piece in particular is forceful and broad-ranging, and produced a really intense, interesting discussion. In it, she moves between land struggles in Lebanon (her home), Syria, and Iraqi Kurdistan, with an analysis through the lens of self-defense. She critiques the positioning of NGOs in the region as ‘feminist’ projects, arguing that by focussing on “empowerment” and the need to “save” women, they do not work to support womens’ self-determination. In particular, Dirik’s interview within her piece had a section on the right to self-defense that we all found very compelling:

In liberalism, in liberal thought and philosophy in general, the expectation is that people should surrender the means of protection to the state. The state should have a monopoly on the use of force. The assumption is that you as an individual member of society should not have the agency to act because the state should decide on your behalf what is dangerous to your existence.

Our discussion that week circled around the replacement of ‘emancipation’ with ‘empowerment’, and how this also appears in the appropriation of ancestral knowledge in the project of nation-building.

The following week, we also read a short piece by PKK founder Abdullah Öcalan, where he coins the term jineolojî. He takes a very firm position on gender, namely that women must form separate political organisations from men if they are to take true political power and resist domination, a practice that has been carried out within the Kurdish struggle. I liked the line “woman’s revolution is a revolution within a revolution”

link: social ecology

Dirik (and Öcalan, and Graeber and Wengrow for that matter) is heavily influenced by the work of American social theorist Murray Bookchin, who coined the term ‘social ecology’, which posits that ecological problems are the end result of structures of social domination, and that one cannot achieve social harmony without ecological, and vice versa. Interestingly, much of the introduction Bookchin gives to the concept circled around conversations we’d already been having, about the dangers of a philosophy of ‘wholeness’ straying into fascistic territory, and the neutralisation of once-radical words.

link: monoculture

Bookchin discusses monoculture in depth as a form of ecological violence that inherits from an ideology of man’s scientific triumph over nature. Similarly to Graeber and Wengrow, Bookchin asks if there is “a scientific discipline that allows for the indiscipline of fancy, imagination, and artfulness? Can it encompass problems created by the social and environmental crises of our time? Can it integrate critique with reconstruction, theory with practice, vision with technique?”.

link: states and nationhood

Both Dirik and Arsanios prompted lengthy discussions about the role of the state in agricultural systems, and the use of ‘nation myths’ in constructing a state. Related to earlier discussions of technology, and the interesting statistic that something like 90% of China’s food is produced on small-scale farms, we decided to read Blockchain Chicken Farm, which discusses the use of technology in rural China. Wang’s writing is rich and evocative, taking a journalistic approach to describing the landscape of Chinese agriculture and technology.

Joseph made the point that so much of China’s historic agricultural policy (early-mid 20th cent), at least that described at the start of the book, is in some way reactive to more global agroecological violence – and it is the state that adapts and in some ways passes that violence down through centralised planning policy.

link: food policy

In our discussion of states and technology, we became interested in reading more about food systems research and the lines of power in global food systems. We discussed Friedman and McMichael’s piece Agriculture and the State System in parallel with Blockchain Chicken Farm – the argument they make is quite detailed, discussing the interplay between agriculture and state systems in the context of transnational capital. They trace the links between colonial relations, newly-independent settler states and the development of the nation-state system along with changes to trade and agricultural specialisation.

The following week, we read an extract from agronomist Marci Baranski’s book The Globalisation of Wheat, on the development of ‘global’ wheat varieties by the American agricultural scientist Norman Bourlag. In the piece, which introduces the project to develop a ‘global’ wheat variety, we wondered what was happening in each of the countries referred to at the time the American wheat research Centres were being set up. It had a bit of an air of ‘oh yeah he just happened to be in Chile in the late 60’s, how interesting’ about it. I think it also charts an interesting transformation to late-20th century colonialism, particularly the part where she observes that the new wheat varieties meant that the agricultural research centres in these countries were effectively de-skilled, as they weren’t developing local varieties anymore but just testing the ‘global’ one.

link: indigenous technoscience

In one session, we had a really interesting discussion on ideas of indigineity, prompted by Åsa’s question of what makes someone not indigenous outside of a settler context, and what ‘ancestral knowledge’ means in the context of a colonial heart like the UK. This also related to the discussion around Meiksins-Wood, about broken links to the land and to one another.

Emilio suggested a piece by indigenous Mexican activist Yasnaya Aguilar Gil, a different approach to technology based on tequio, an ideology of technology based on sustainable and collective action. In particular, she cites the repurposing and adaptation of technologies within Abya Yala (the indigenous name for Central and South America), the development of open-source tools and the resistance to cell phone giants as examples of the use of technology as a form of mutual support. Reflecting on this text, we also talked not just about digital technology but forms of knowledge transfer in general, thinking about alternatives to written text as ways to contain and mediate knowledge.

This also related to the Graeber and Wengrow text – so many nomadic societies don’t make it into the archaeological record because they didn’t build permeanent structures – meaning that their histories aren’t legible to, and thus not included in, the archeological narrative.

Gil also addresses the false environmentalism of extractive ‘green technologies’, e.g. mining for rare earth minerals on indigenous lands.

link: neocolonialism

There’s a remarkable part of the Cabral question-and-answer session, where he discusses why Portugal has not been able to relinquish Guinéa and Cape Verde as colonies:

…it is precisely because Portugal is underdeveloped, that she is unable to find a solution for her colonies, because she cannot hope for a neocolonialist one. In analysing the problems of African independence we can say that independence was given to colonised countries by the colonial powers as a means of securing the indirect domination of colonised peoples. But Portugal does notpossess the necessary economic infrastructure that will allow her to try decolonisation in this manner. She cannot decolonise because she cannot neocolonise.

This notion of neocolonial power relations came up in many places, but in particular in a text introduced by Joseph and Stéphane, about the deployment of national parks in Africa as part of a neocolonialist land grab, under the guise of ‘environmentalism’.

Where next?

We finished up the season on Baranski and Silvia Federici, but we didn’t have a proper discussion of the latter so we’ll start next season with that too. I’d like to read some Vandana Shiva and potentially some more economic/political analysis too – Jeffrey M. Paige’s book Agrarian Revolutions looks interesting in this regard. I’d also like to read more on logistics and supply chains, following on from the food systems readings toward the end of the season, and Cabral’s economic analysis. Moten and Harney’s All Incomplete might be a place to start, and Denise Ferreria de Silva’s work.

With love and thanks to Åsa, Maya, David, Cherry, Emilio, Stéphane, Joseph, Derek, Moza and Andrew for participation in and contributions to ARRG A/W 2022.