on peaceful and noisy machines

This year, I’ve been involved in making two different synthesisers. The first of these has been a collaboration with the electronic musician John Richards, aka the Dirty Electronics Ensemble with artwork by Colin Therlemont (Tellamont). The project is called More Roar, and the synth is a digital frequency modulation synthesiser built using a STM32 microcontroller.

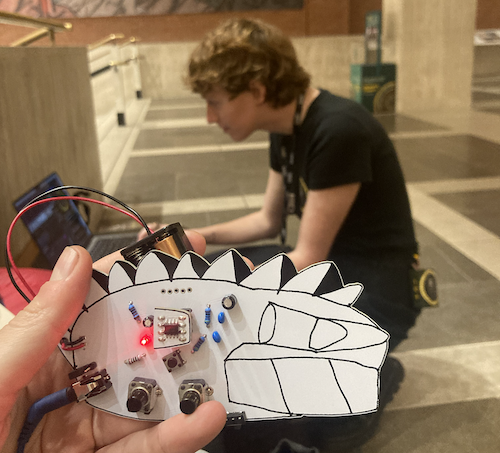

the More Roar synth in its final form (sans chip, which is broken off as a tooth)

the More Roar synth in its final form (sans chip, which is broken off as a tooth)

The second was made by me for a new performance by the Commission for New and Old Art (heareafter: the Commission). The whole performance was called Valves; the synth was for a new piece called On Pendle Hill, composed by Oliver Vibrans. The synth itself never really got a name, though collectively we started to refer to it as the Machine.

In both cases, I’ve been thinking a lot about the political nature of different technologies, technology’s militariness and the resistance to military co-optation of work made using technical things. These concerns feel particularly urgent in the context of the genocide in Gaza and the occupation of the West Bank. Military technologies are not just the drones (manufactured in Britain), the guns and bombs used to kill Palestinians, or even the Israeli surveillance infrastructure built by Google and Amazon, but the systems of capital and convenience that sustain this status quo.

My original training is in electronic engineering, and I still subscribe to the IET’sthe Institution of Engineering and Technology, one of Britain’s biggest professional accreditation bodies for engineers jobs mailing list – these days, it’s almost entirely dominated by weapons companies. I always remember my friend Angela describing the presence of Elbit Systems in Britain as ‘creepy’, this sense of a close proximity to violence feeling deeply uncomfortable and unsettling. Moving back toward electronics (after years of mostly making work with the web) I find myself wanting to understand and use technologies where the overlap (in expertise, documentation, components) feels much closer to this militarised domain of engineering. Being closer to the source means being confronted with the decisions that a lot of technologies keep hidden, and getting, on some level to decide them for yourself.

Valves

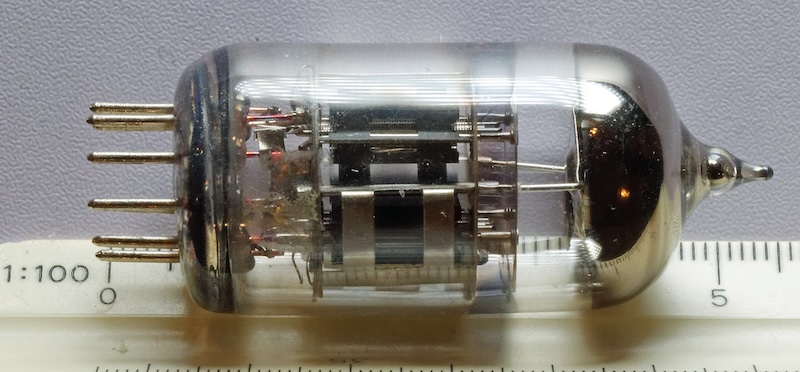

the 12AX7 vacuum tube

the 12AX7 vacuum tube

Some of the initial ideas for the Valves synthesiser came from a conversation with Sam Fairbrother of the Commission a couple of years ago, where, during a conversation about artificial intelligence he asked me “Can you make a peaceful machine?” – eg, is it possible to make a pacifist technology. I found the question very difficult to answer, and still do.

Valves as a performance circulated around the valve as a unifying theme through post industrial areas of Northern England. Most of the performance centred around brass instruments, with the brass band in particular as a symbol of Northern industrial heritage. In keeping with the theme, the specific requirement for this synthesiser was that it be made using a vacuum tube – a thermionic valve. STAT magazine wrote about the whole performance here.

Lydia and I performing in On Pendle Hill (photo: Brad Morgan)

Lydia and I performing in On Pendle Hill (photo: Brad Morgan)

Vacuum tubes are really interesting components to work with. As the ‘valve’ moniker suggests, they work by controlling the flow of a medium: similar to transistors, they use a small electrical current to switch a much larger one, effectively working as an amplifier. Vacuum tubes have been almost entirely superceded by transistors, but not because they didn’t work – they were ultimately abandoned due to size, cost and practicality. They aren’t as ‘clean’ as amplifying components as transistors are – they add to the sound, but in a way that can be very appealing for audio signals, and is considered quite ‘rich’ – which is why you still find them in guitar amplifiers.

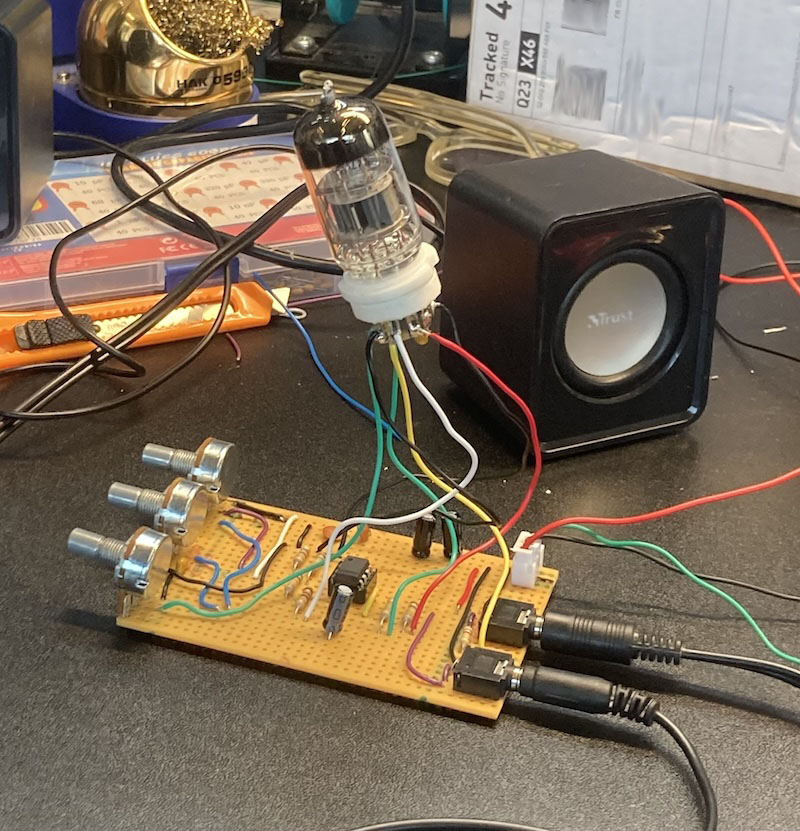

The eventual design was based on a design by Look Mum No Computer called the Safety Valve, that uses a vacuum tube called the 12AX7, which can be driven at 12V, making it much safer to power. It consisted of two valve stages – a distortion module, and a Voltage Controlled Amplifier (VCA), which were fed by two tone generators (hacked together from the More Roar synth), modulating the two signals together. The resultant sound is really interesting – in both cases (the VCA is just a kind of modded variant of the distortion module) the valve acts as a kind of imperfect amplifier, replicating the signal but adding multiple layers of harmonics. It works best with very simple sounds, adding a richness and a crunchiness to even very basic tones.

testing the first distortion module of the valve synth

testing the first distortion module of the valve synth

On Pendle Hill

On Pendle Hill is a piece composed for baritone horn, brass chorus, valve synthesiser and clogs. The horn and brass chorus were performed by Troy Kelly and the Hebden Bridge Brass Band, with Lydia Phillips and I playing the synth and Sam Fairbrother clogging. The piece also included an audio recording of Ellie Kinney, a peace activist, from the top of Pendle Hill, narrating her view of a landscape that contains multiple weapons factories, and her view of the Northwestern England as a specifically militarised industrial zone.

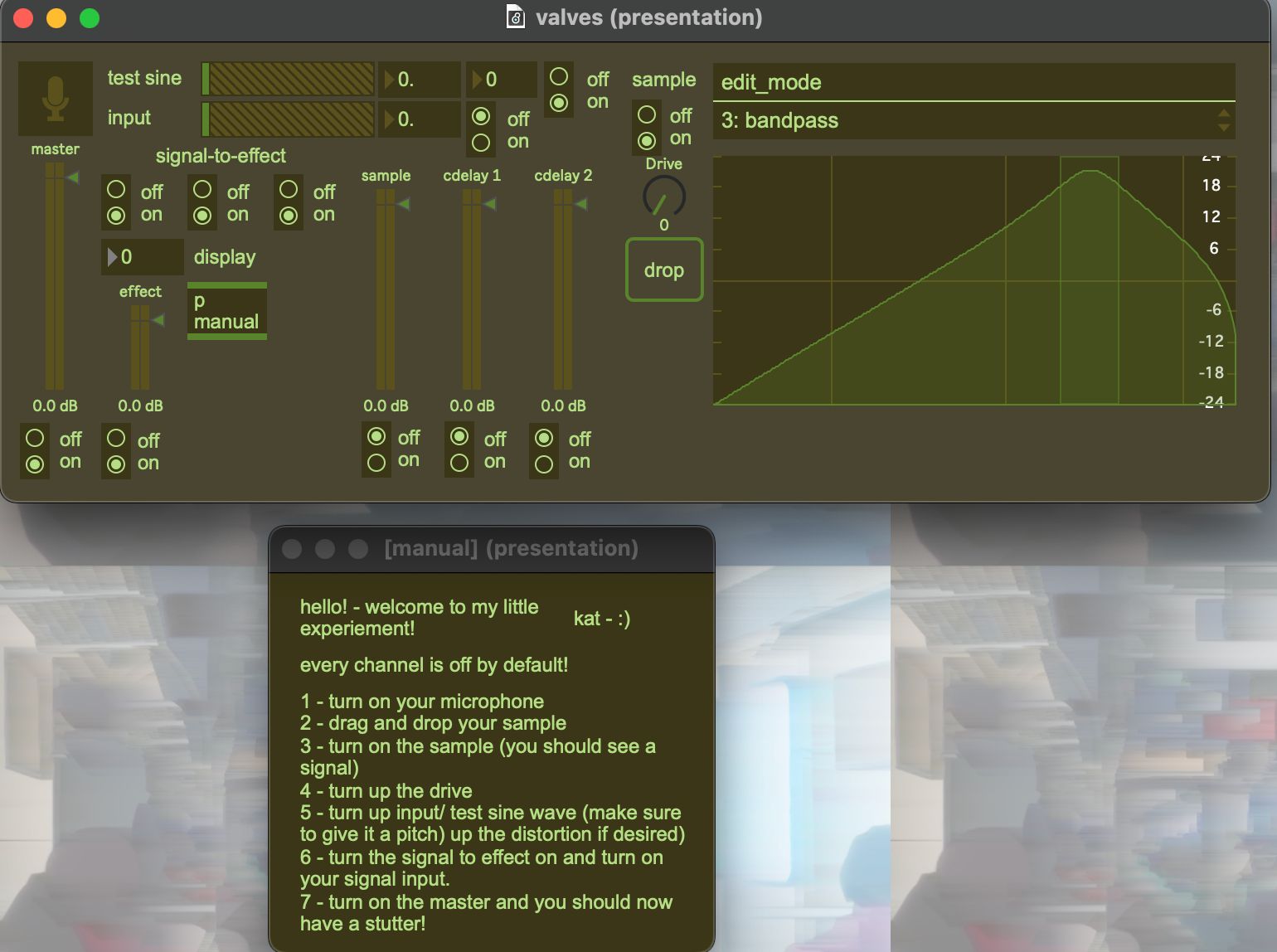

A lot of the ideas about the synthesiser (and the sound texture we made with it!), developed in conversation with Lydia Philips and Kat Macdonald. The first part of the synth I made was the distortion pedal, and in initial rehearsals we prototyped the VCA using some Max software that Kat made. We had an initial idea to modulate the signal using footsteps, which sounded great in the digital software, but the valve VCA brought in so many extra harmonics that it proved too noisy in practice.

Here are some test samples we made with the final synth setup, using two sine tones as input to the VCA.

Much of our discussion circulated around the synth and the broader performance’s military-industry-hardware-sound relationship. There’s a lot there – Raytheon, the world’s largest defence contractor, was initially a vacuum tube manufacturing company. The 12AX7, the vacuum tube is a close relative of the 12AU7 – a miniaturised equivalent of which (6111) was apparently developed for their Sidewinder missile in the mid-1950s. Meanwhile, the ‘great Northern industry’ that the brass band has historically symbolised increasingly consists of weapons manufacturers, including Elbit and Raytheon. Throughout the piece and the performance more generally there’s a deep ambivalence that never really resolves.

Hebden Bridge Brass Band marching into The White Hotel (photo: Brad Morgan)

Hebden Bridge Brass Band marching into The White Hotel (photo: Brad Morgan)

At the end of the program notes for Valves, we included a line “we’d like to think there’s another way”. In technical teaching, I think there’s something important in showing that there are many ways to do things – it helps to understand technical things not as monolithic tools, but rather (to paraphrase a nice essay by Cristóbal Sciutto), a medium that one can have a degree of agency over.

This sense of agency is, I think, a necessary but not sufficient condition for the revolutionary use of technology. Using a piece of technology without having a sense of how it works means that many of the decisions that went into it, and the way it acts in the world are opaque, making it harder to act with intention.

More Roar

hedgehog plus Kat in the wild (at an LCLO rehearsal)

hedgehog plus Kat in the wild (at an LCLO rehearsal)

More Roar was developed specifically in an artistic/educational context. In March this year, I invited John to come to the CCI to run a synth-building workshop for our students. I’d remembered going to one of John’s workshops as an electronic engineering undergraduate, and experiencing electronics as this totally different, vibrant thing. I loved (and still do love) the maths and theory of electronics, but there was a liveness to the synth that we made that felt very different, and quite transformative.

John decided to use this as an opportunity to develop code for a chip he’d not worked with before, and after some discussion he settled on the STM32 microcontroller, which had recently been made available as a tiny 8-pin package. After the workshop, he asked if I’d be interested in developing it further into a project together. Much of my contribution to the project has been to write the code for the FM synthesis algorithm, and later the decay function that periodically adds noise to the signal. This was a very enjoyable process of writing some ultimately quite simple code. It’s humbling to come back to microcontrollers after about a decade away and realise just how theoretical and ungrounded your engineering education was.

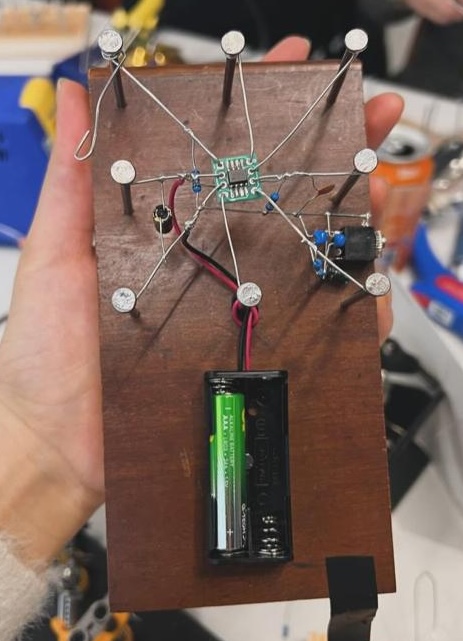

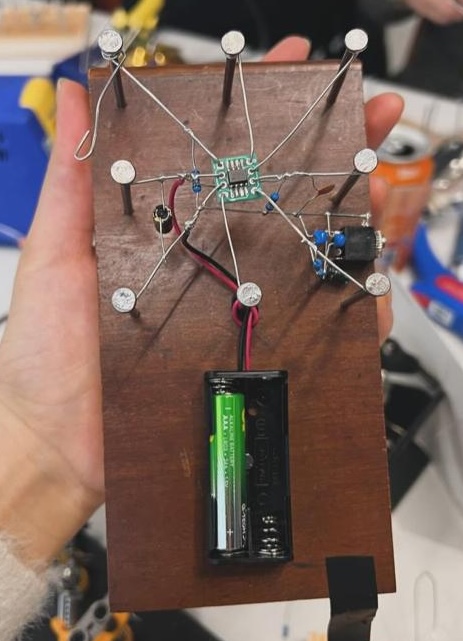

the DIY nails version of the synth from John’s initial workshop at the CCI

the DIY nails version of the synth from John’s initial workshop at the CCI

The synth has three control inputs – two dials, which control the frequency of the signals modulated by the synth, and a button that switches the mode. The sound is generated using the Direct Digital Synthesis algorithm, and benefits from the speed of the chip used, one of the key features that made it appealing. It’s become affectionately referred to as the ‘hedgehog’ after Colin’s design, which has given the sounds a really nice character. The hedgehog follows months of breadboard prototypes, plus the ‘nails’ type synth of John’s design that we made with the students (that suspends the chip between 8 nails, and uses capacitance instead of potentiometers for the analog inputs). John wrote a document for the November iteration that you can find here.

The synth makes a range of sounds – it’s kind of amazing how much you can get out of even a simple algorithm – with an emphasis on sounds that are quite digital (scrapy/beepy), and quite monumental (windy/wet/weathery). The more you change the mode, the more the signals used decay – eventually they rot down to nothing – with the decay rate and mode changing every time the synth is turned on. I think one thing that appeals about this quality is to make an instrument with a sensibility that you have to attune to and recognise – to see when it’s rotting faster or slower, to understand how the modes work.

John and I performing at Paradise Palms

John and I performing at Paradise Palms

This sense of skill in practice is also something that makes me want to make more electronic objects with my students. Currently in my department, the electronics education most of our students recieve involves learning Arduino, perhaps experimenting with other boards (like the ESP32) or the Raspberry Pi. There’s something very exciting about handing a student a bare chip, show them how to program it using just a text editor. There’s something very liberating about that process.

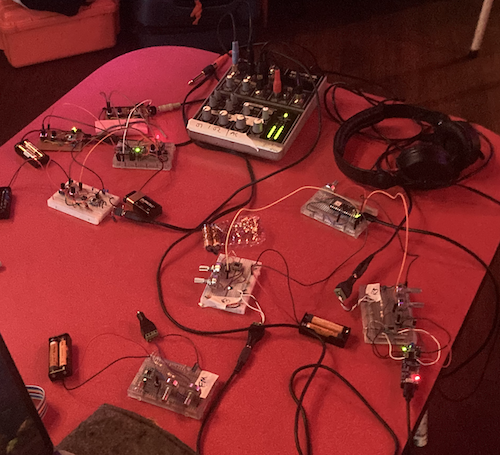

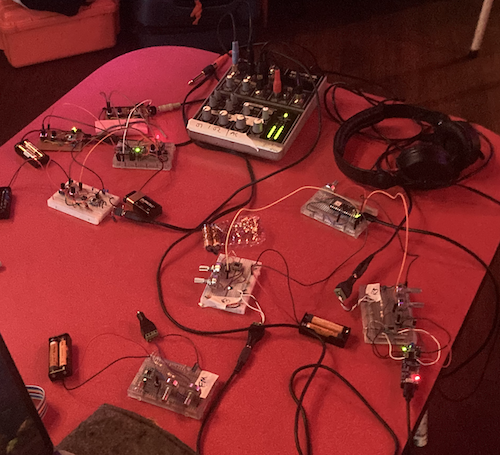

gig setup with four breadboards

gig setup with four breadboards

John decided to use this as an opportunity to develop code for a chip he’d not worked with before, and after some discussion he settled on the STM32 microcontroller, which had recently been made available as a tiny 8-pin package. After the workshop, he asked if I’d be interested in developing it further into a project together. Much of my contribution to the project has been to write the code for the FM synthesis algorithm, and later the decay function that periodically adds noise to the signal. This was a very enjoyable process of writing some ultimately quite simple code. It’s humbling to come back to microcontrollers after about a decade away and realise just how theoretical and ungrounded your engineering education was.

the DIY nails version of the synth from John’s initial workshop at the CCI

the DIY nails version of the synth from John’s initial workshop at the CCI

The synth has three control inputs – two dials, which control the frequency of the signals modulated by the synth, and a button that switches the mode. The sound is generated using the Direct Digital Synthesis algorithm, and benefits from the speed of the chip used, one of the key features that made it appealing. It’s become affectionately referred to as the ‘hedgehog’ after Colin’s design, which has given the sounds a really nice character. The hedgehog follows months of breadboard prototypes, plus the ‘nails’ type synth of John’s design that we made with the students (that suspends the chip between 8 nails, and uses capacitance instead of potentiometers for the analog inputs). John wrote a document for the November iteration that you can find here.

The synth makes a range of sounds – it’s kind of amazing how much you can get out of even a simple algorithm – with an emphasis on sounds that are quite digital (scrapy/beepy), and quite monumental (windy/wet/weathery). The more you change the mode, the more the signals used decay – eventually they rot down to nothing – with the decay rate and mode changing every time the synth is turned on. I think one thing that appeals about this quality is to make an instrument with a sensibility that you have to attune to and recognise – to see when it’s rotting faster or slower, to understand how the modes work.

John and I performing at Paradise Palms

John and I performing at Paradise Palms

This sense of skill in practice is also something that makes me want to make more electronic objects with my students. Currently in my department, the electronics education most of our students recieve involves learning Arduino, perhaps experimenting with other boards (like the ESP32) or the Raspberry Pi. There’s something very exciting about handing a student a bare chip, show them how to program it using just a text editor. There’s something very liberating about that process.

gig setup with four breadboards

gig setup with four breadboards

Microcontrollers are funny things, as they bring you much more directly into contact with control over a medium (movement of electrons around a piece of silicon) and in the process highlight just how far removed from the medium you yourself are. A lot of John’s work that I really appreciate is taking these chips that cost about £2 and maximising the kind of sounds they can make. One thing lots of people say to me is, how does something that small make such a big sound?

Last November we performed a small gig in Hackney as part of the NonClassical birthday party, with 4 of the synths feeding into a mixer, and a couple of homemade sequencers controlling the mode switching. It was deeply fun as an experience, and worked surprisingly well despite very little practice time. It felt in a way like much of the performance was already in the instrument, and we were just bringing it out. Perhaps this is contradictory to the idea of it being an instrument that requires skill to play, though perhaps also it’s a creature that we are both already very familiar with. We are still tweaking the code, but plan to release the synth early next year.

Back in November I went up to Leicester to visit John and record some samples. What you’re hearing in these is 2 or 3 of the synths playing together, plus some input from a sequencer to drive them in time, but no other sounds or inputs.

I think there’s something between both these projects – about making full use of something, that’s either small, or defunct, and trying to find the limits of its possibility – that feels like a way to answer the question about peaceful machines. In the manifesto on the Commission’s website, in arguing for the restaging of old works, they claim that that “developments of the past 150 years have been made too expensive, rarified, or fossilised”. So much of the basic violence of technology is in its extractiveness and newness, the constant refreshing and waste, of expertise that degrades and disappears – and a willingness to disregard human life (human-ness!) in the pursuit of this newness.

I recently really enjoyed Tetsuo Kogawa’s essay on DIY micro-radio Toward Polymorphous Radio, in which he paraphrases Heidegger to ask ‘What is radio’s “most extreme possibility?”‘, describing decades of work hosting microbroadcast radio stations on homemade transmitters. What I like about it so much is that the relationship to newness is totally there, but transformed. Micro radio is not new technology, but an old technology used to its fullest extent, over a long period of time, with results that are very surprising.

Research materials for Valves are here, and for More Roar here. I was particularly delighted for both projects to have come across the Modwiggler forum, has a lot of really helpful DIY synth resources